There’s a pull to studio portraits that’s always had me hooked. It’s not just a face, it’s a whole world caught in a frame, shaped by clever lighting, a thoughtful pose, and a photographer’s quiet spark, my first introduction to the studio portrait was my school photos, from nursery right up until I left school after 5th year in 1993 but there’s something romantic about the idea of a nineteenth-century studio: heavy drapes framing the scene, props artfully arranged, and the soft glow of gas lamps lending an almost ethereal quality to the environment. The studio portrait was born here, a revolution that took portraiture away from the exclusive domain of painters and made it something the everyday person could afford. It was groundbreaking, a way for families, individuals, and communities to see themselves immortalised for the first time. No longer limited to the wealthiest few, portraiture became a way for people to assert their identities, mark significant moments, and leave a tangible legacy.

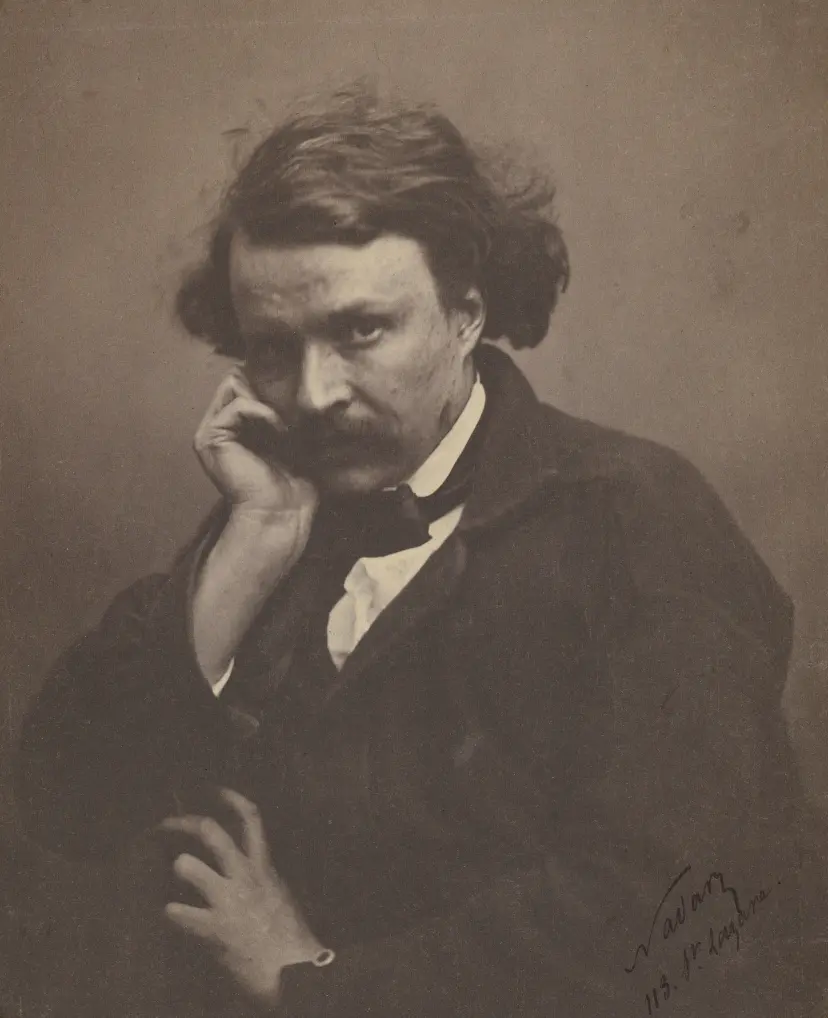

The dawn of the studio portrait coincided with the rise of the daguerreotype, introduced in 1839 by Louis Daguerre. The daguerreotype was a marvel, producing stunningly detailed, one-of-a-kind images on polished silver-plated copper. However, the method was far from simple. Long exposure times required subjects to remain perfectly still, which is why so many early portraits carry a solemn, even stiff, tone. But these limitations didn’t stop photographers of the era. In fact, they leaned into them, transforming their studios into spaces of artistry and invention. Photographers like Nadar in Paris and Mathew Brady in the United States weren’t just taking pictures; they were carefully crafting scenes. The right backdrop, the perfect pose, the manipulation of natural light, all of it was a deliberate process that made each portrait feel like a work of art.

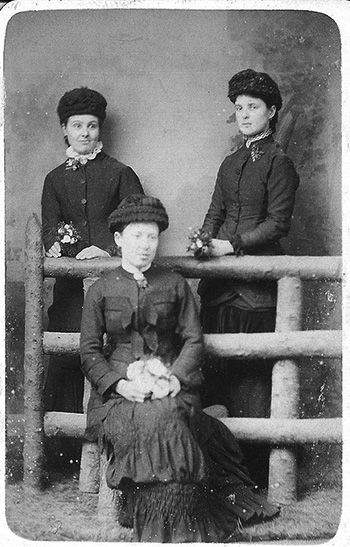

I like to imagine stepping into one of those early studios. The sense of occasion must have been palpable. Sitting for a portrait wasn’t just another part of the day; it was an event, almost ceremonial in nature. Families would dress in their finest, eager to create a lasting image that would be treasured for generations. The process could be painstaking, with photographers battling the technical limitations of the time, but the results were worth it. Those early portraits carry an almost sacred quality, a quiet dignity that speaks to the care and effort poured into every detail.

In the 1850s, the wet collodion process changed the game. Invented by Frederick Scott Archer, this method allowed for sharper images and, crucially, the ability to produce multiple prints from a single glass negative. The catch was that the entire process, coating the glass plate, taking the photo, and developing it had to be done before the plate dried. It was a race against time, and yet, the results were astonishing. For the first time, photographers could make their work more widely available, and studio portraiture flourished. Studios began cropping up in cities and towns, their lavish interiors offering a sanctuary where subjects could step away from the chaos of daily life and into the carefully curated world of the photographer.

By the late 19th century, dry plate photography had replaced the wet collodion process, making the photographer’s life a little easier. This advancement, coupled with improvements in printing technology, allowed for even more creativity in the studio. Photographers experimented with lighting, composition, and props, pushing the boundaries of what a portrait could convey. These weren’t just images; they were statements, expressions of pride, status, or sentimentality. The studio portrait became a platform for self-representation, and photographers embraced their role as both documentarians and artists.

What I find most moving about these portraits is their ability to convey emotion. With the technological advances of the time, photographers could capture subtleties that brought their subjects to life. Locking eyes with a portrait from 150 years ago can feel like stepping into a time machine. There’s an intimacy, a humanity, which transcends the years. It’s a feeling I try to emulate every time I compose a portrait, whether I’m shooting family on a lazy Sunday or carefully arranging a more formal setup.

Studio portraits stand as a testament to the value of deliberate artisanry. In our modern era of instant photography, where snapping and sharing takes seconds, the slow, intentional process of the studio portrait feels almost radical. It’s a sentiment I carry with me, whether I’m adjusting the exposure on my DSLR or fiddling with Lightroom sliders to perfect an image. A good portrait is never just a picture; it’s a dialogue, a moment of connection between photographer and subject. It’s about capturing not just how someone looks, but who they are.

Before the rise of the studio portrait, images of individuals were a luxury reserved for the elite. Wealthy patrons might commission a painted portrait, but for the average person, the idea of having one’s likeness preserved was almost unthinkable. The advent of studio photography changed all of that. It democratised the portrait, offering a mirror instead of a mask. Photographers used every tool at their disposal, reflectors to soften shadows, diffused lighting to flatter features to create images that were as revealing as they were aspirational. Today, when I’m editing a photo or adjusting the light, I often think of those early innovators and the painstaking care they took with every shot.

The studio portrait also plays an essential role in how we remember history. The iconic images of stern-faced Victorians, with their unwavering gazes and intricate attire, were largely the work of studio photographers. These portraits provide a window into the past, capturing not just individuals but the essence of an era. They remind us of photography’s power to document and interpret life, a power that continues to inspire me every time I pick up my camera.

As the 20th century approached, the studio portrait continued to evolve. Photographers began to experiment with bolder lighting techniques, unconventional poses, and new approaches to composition. The art form proved itself adaptable, alive, and responsive to the changing times. That adaptability is something I strive to carry into my own work. The principles of those early photographers, careful composition, mastery of light, and a focus on capturing true emotion remain my guiding stars.

For me, the studio portrait is deeply personal. Setting up a shot, tweaking the light, and waiting for the perfect moment feels like stepping into a tradition that stretches back nearly two centuries. It’s a way to pause, to connect, to create something that resonates beyond the frame. From casual phone snaps around Aberdeen to more deliberate DSLR sessions, the lessons of studio portraiture are always there. They’ve taught me patience, attention to detail, and the importance of seeing beyond the surface.

At its core, the studio portrait is a celebration of individuality. Each frame tells a story, not just of the subject but of the photographer’s vision and the time in which it was created. It’s a legacy I’m honoured to be part of, blending the wisdom of the past with the possibilities of modern technology. Every time I pick up my Nikon, I feel that connection to those early trailblazers, their sweat and dedication still echoing in the work we do today.

The studio portrait isn’t just a chapter in photography’s history, it’s its beating heart. It’s the moment when photography moved beyond science and became an art form, capable of capturing not just how we look but who we are. For me, it’s a reminder that every portrait is a story waiting to be told, a chance to honour the human experience in all its complexity and beauty. As I continue my journey in photography, I’m grateful for the lessons of the studio portrait, and I can’t wait to see where they lead me next.

Regards

Alex