Opening these pages from The Exposed Eye feels like a profound act of archaeology. I have to admit my oversights in not lingering longer to uncover the unspoken narratives that haunt the frame sometimes. These images, woven into Härenstam and Strand’s playful yet profound dialogue, resonate deeply with my passion for photography’s ability to peel back layers of identity and memory, prompting deeper reflections on the fragility of belonging in a world of concealed truths and impermanent connections.

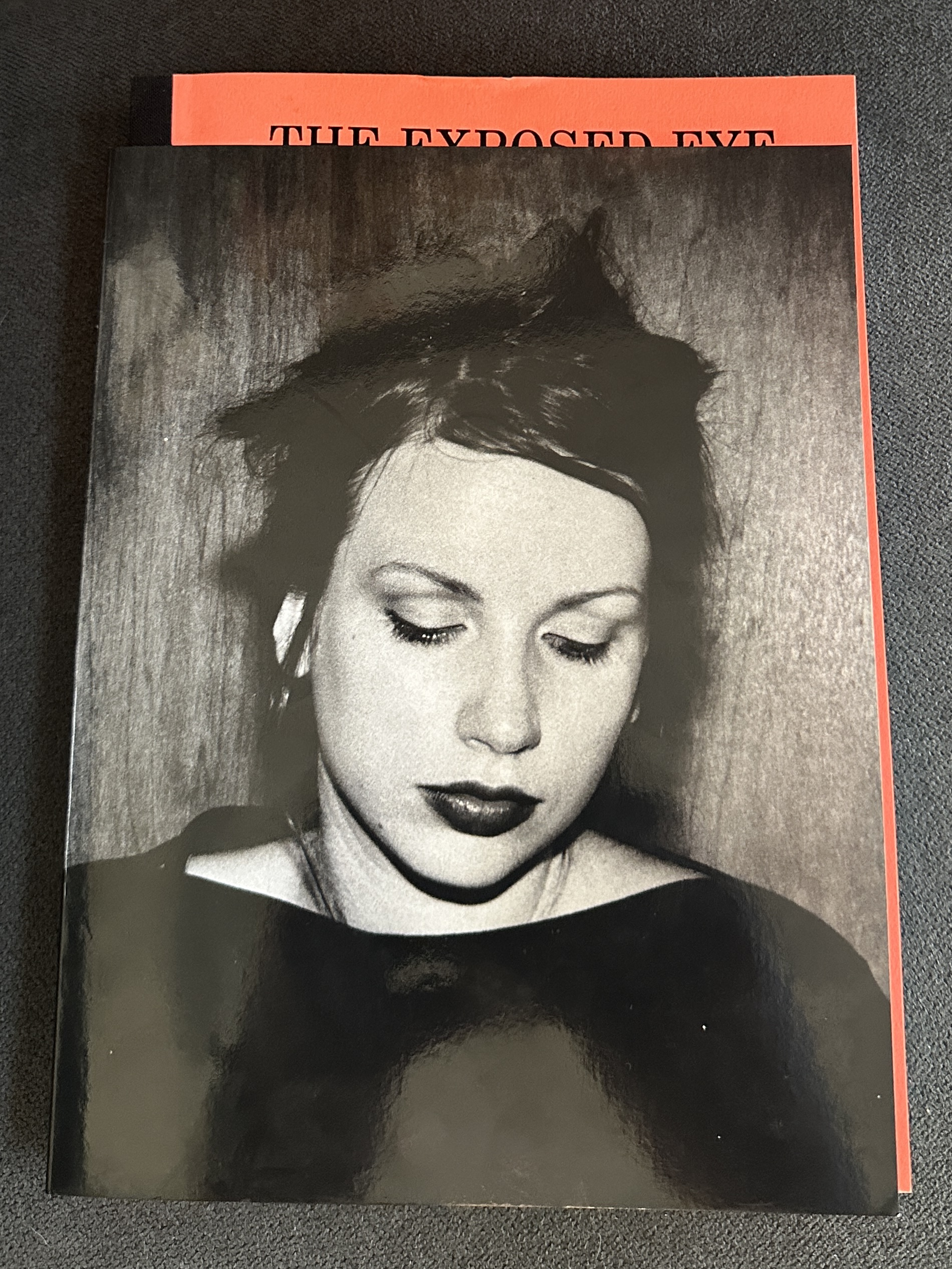

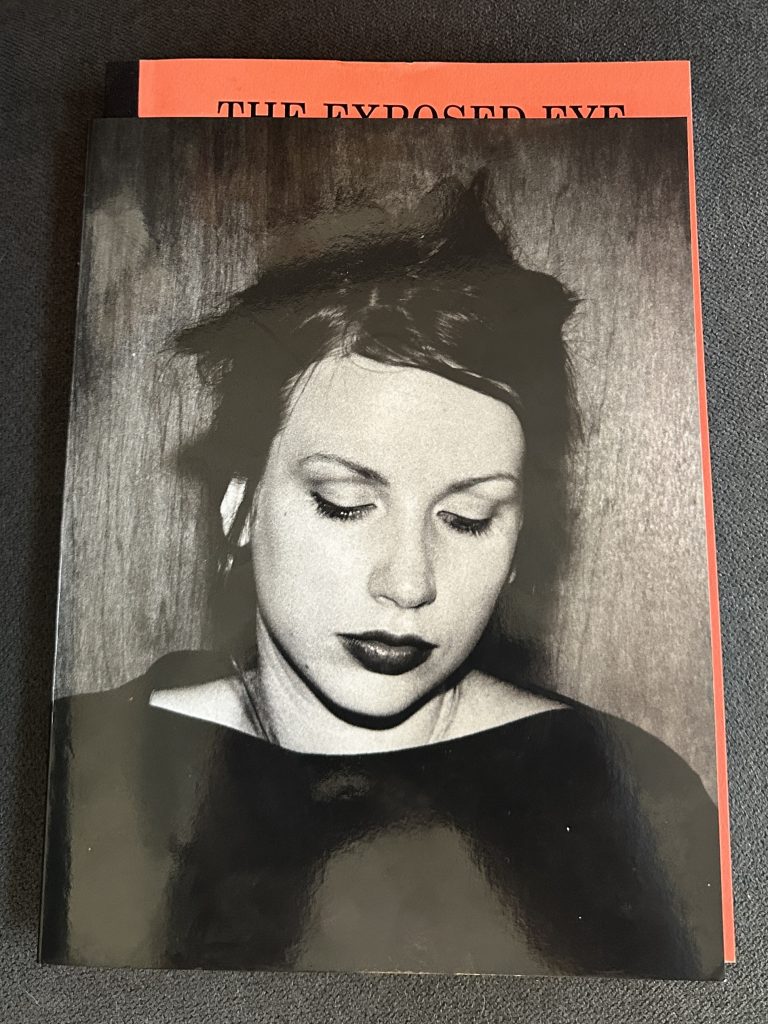

This book, a tactile and understated great from Sailor Press, feels like unearthing a journal. It presents eighteen assignments, a yearlong chain of spontaneous, reciprocal challenges between two artists. The book’s softcover form, with its Swiss binding, invites intimate flipping, allowing the images and text to breathe across double spreads, prioritising narrative flow over ostentation. The artists’ method is fascinating, blending analogue captures, found elements, and digital interventions. This work provokes contemplations on the fluidity of identity through playful alter egos and metamorphoses, the weight of memory, and the raw undercurrents of vulnerability in confronting death and desire. They take us from the man called Raftworks Abrahamsson, who walked on water with his own poetic invention, to the quiet terrors of a father disappearing before he dies. They travel through realities and escapes, among children, x-rays, and even cyclopes.

Let us immerse ourselves in some of these vignettes. One assignment is about Raftworks Abrahamsson, a man who, in 1934, built a set of “raftwork skis” and recited poetry while walking on the Vindel River. This simple prompt opens a vast exploration of a character who was called a “village idiot,” “eccentric,” and even “Crazy Abe”. The artist ponders how this man navigated a world that saw him as a failure. It reminds her of her own struggles with feeling out of place, a sentiment rooted in her youth when others tried to define her by her speech or her body. This segues assignment Two and EURIKA! With a devastatingly honest reflection on a father’s descent into illness. The artist’s father, a professor, began to talk to himself in different languages, repeating that he was a “failure” and “worthless”. To cope, the artist imagined they were talking to Archimedes, a cartoon the father drew of an old man in a bathtub. This poignant act of self-preservation gave way to the heartbreaking realisation that the father she knew “wasn’t coming back”. She grappled with the idea of a person “disappearing before you actually die,” a possibility she had never considered. The image of this artist using tippex/white-out on her father’s old cartoons to write in his new, transformed words is a gut punch, a visceral testament to the process of grieving a living person.

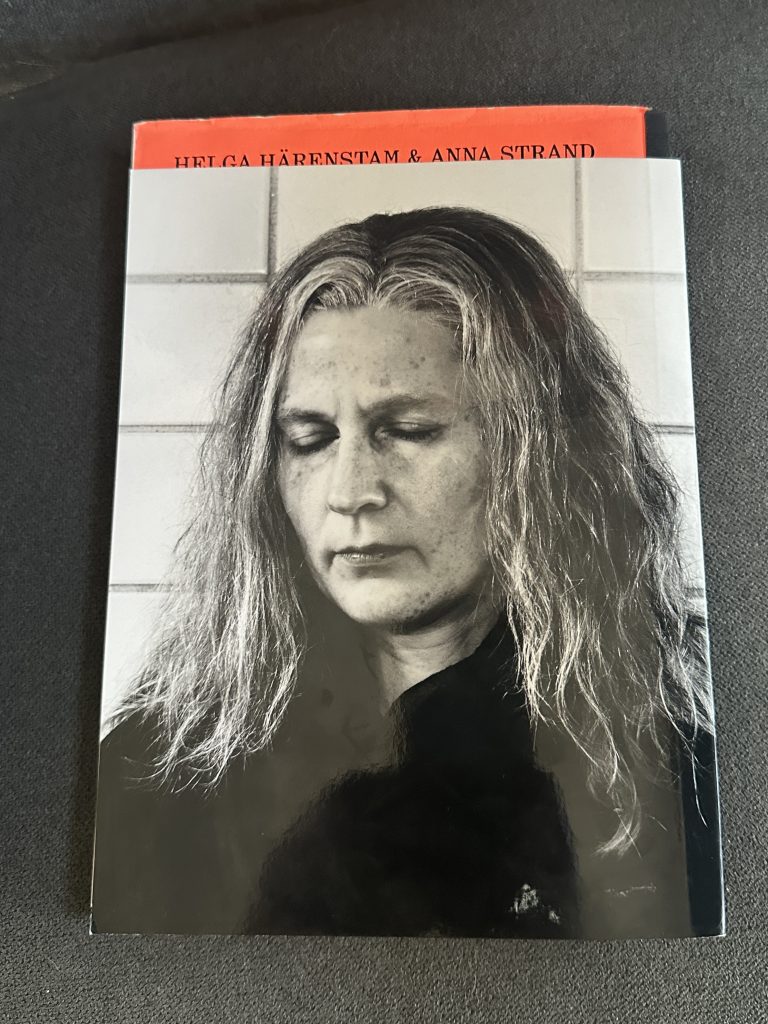

Another assignment, prompted by a “moose”, turns into an unvarnished and surprising conversation with an uncle about hunting. He reveals the “macho attitude” around the hunt, where hunters aren’t supposed to act sad or be seen as “soft”. The uncle, who never even shot a moose, talks about the pressure to be decisive, to not hesitate when the animal is looking at you. This dialogue peels back the layers of societal expectations and gender roles, a theme that echoes throughout the book. We see this again in the “BANG BANG!” assignment, which explores the presence of violence in children’s play. The artist reflects on her own childhood, where she realised, she was “read” as a boy and solved the problem by getting her ears pierced. This is a profound and melancholic reflection on the subtle ways we change ourselves to fit into the world and appease others.

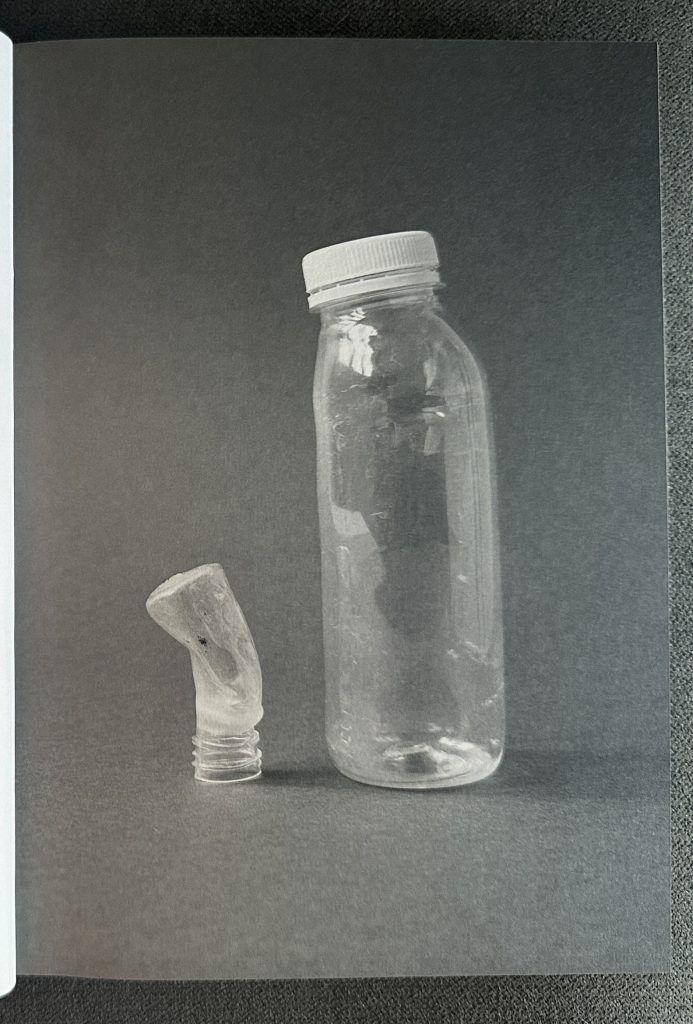

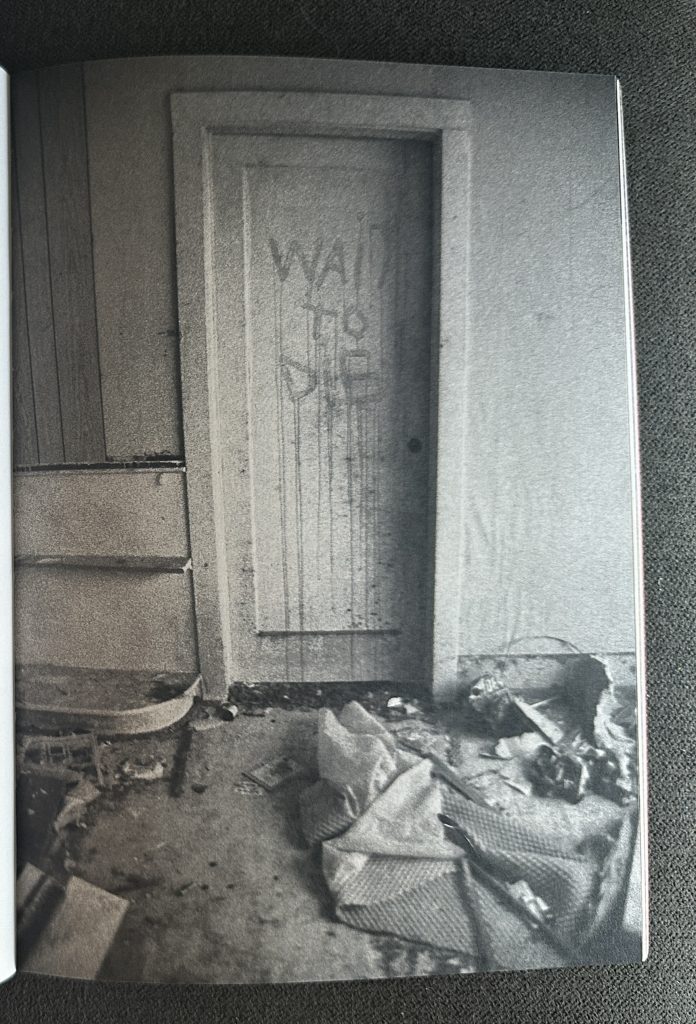

One image from the book that I love is a stark black and white study of translucent plastic forms. A tall empty bottle stands sentinel beside a smaller, bent neck fragment. The minimalist elegance of the frame, with shadows playing softly, transforms this discarded remnant into a commentary on fragility and impermanence. I treasure this for its poignant simplicity, and because to a lot of people it is just empty bottles except it’s not and is at the same time. It raises a question about societal waste and our own transient existences. Another haunting photograph confronts us with a derelict interior and a weathered door etched with the words “WAIT TO DIE”. The composition is great, an unflinching stare into oblivion. It echoes my own graveyard wanderings, where inscriptions on stones stir reflections on time’s erasure. It is a testament to the artists’ immersive approach of seeking out forsaken spaces to humanise impermanence, reigniting my admiration for works that challenge us to confront life’s fleeting curtain call.

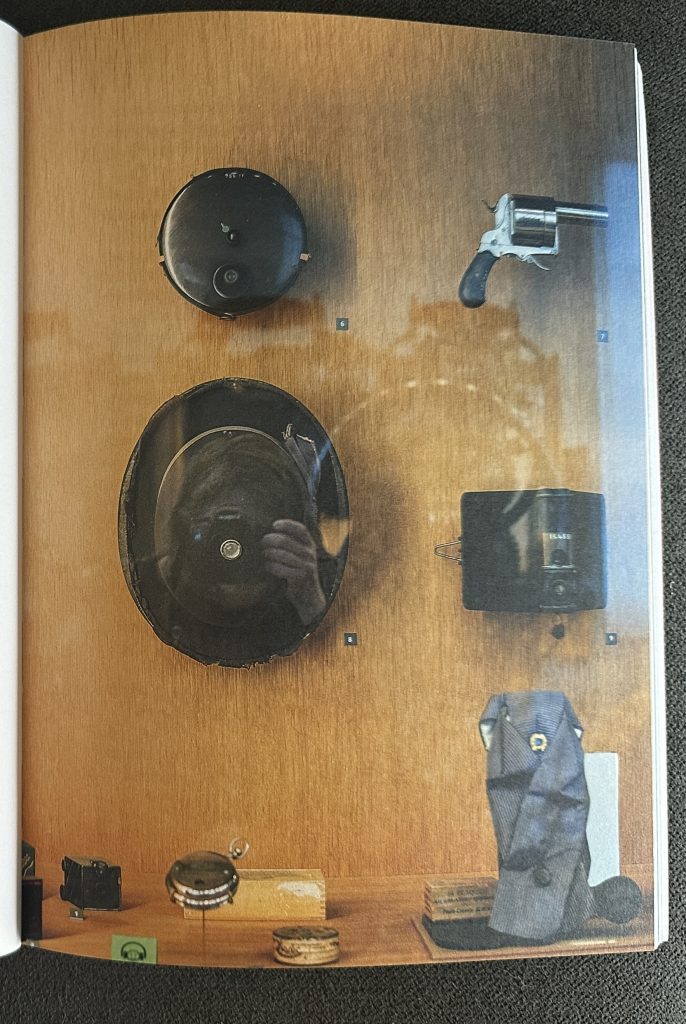

The book’s raw honesty and profound insights come from the artists’ willingness to be vulnerable. In an assignment about Superpowers where they go to Paris, one recounts being disappointed after trying to take pictures with a secret camera pen, only to find she had mostly recorded the “inside of my own coat pocket”. Instead of good images, she got a “digital crackling sound” and footsteps. It is a humble and relatable moment of failure, reminding me of my own photographic missteps and the beautiful, often unexpected, things that come from them.

In the end, these vignettes from The Exposed Eye renew my hunger to embrace photography’s defiant gaze into the unseen, reminding me to look more into “Art” as a whole and not just photography but all sections of it and it is urging us all to linger in those liminal spaces where truth appears unbidden. Ultimately, this volume rekindles my faith in photography’s defiant magic to illuminate life’s concealed rhythms. It compels us to venture into our own uncharted assignments with unyielding curiosity.

Regards

Alex