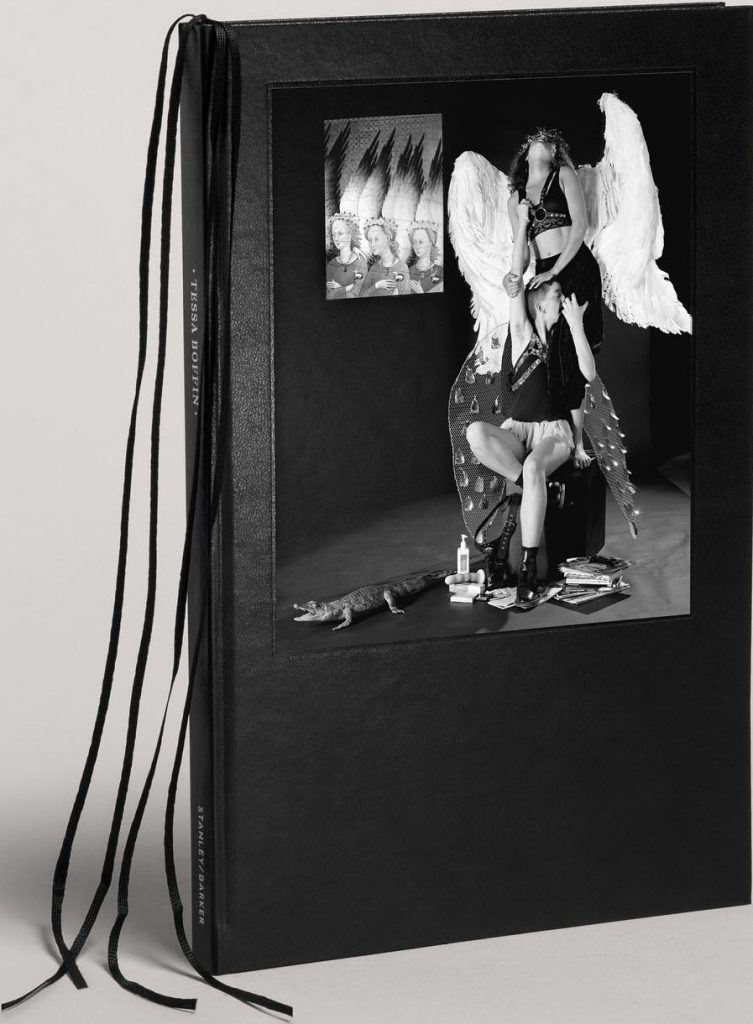

Tessa Boffin, edited by Sunil Gupta for Stanley/Barker is not a book one simply reads; it is a visceral, philosophical declaration of war against shame, silence, and institutional neglect. Presented with the care and unflinching honesty we expect from Stanley Barker, this book arrives less as an archive and more as a powerful, necessary call to arms, a brilliant monument to a generation’s defiance. It hits with an immediate, resonance that goes directly to the heart of my own photographic philosophy.

I love trying to capture human stories, from the raw intimacy of portraiture to the socio-political weight of protest documentation. In Boffin’s work, I see the ultimate, electrifying expression of that struggle. While I often rely on the “found” decisive moment, Boffin proves that sometimes, the only way to capture the truth is to fabricate it, to stage it with such fierce, intentional artistry that it becomes more real than any candid snapshot could ever be. Her images, forged in the crucible of the late 80s and early 90s AIDS pandemic, are active weapons. They are a defiant refusal to accept the heteronormative, fear driven narratives imposed by the media and government, and that spirit of visible resistance is exactly the soul settling way of seeing that I constantly seek out. This book is a reminder that the most potent art is often forged in moments of crisis, driven by a desperate need for survival and the courageous reclamation of one’s own body and story.

Boffin’s work begins with an aesthetic rejection of objective realism, opting instead for a theatrical, yet profoundly honest, gaze that turns the body, the site of epidemic and shaming, into a location of defiant, ecstatic desire. This is a necessary and strategic move.

The textures in the book of dark, sensual fabric against the skin, rendered with that dramatic, almost Baroque chiaroscuro lighting, turns images into a political canvas. This is the body, the object of fear and moral judgement during the pandemic, being defiantly reclaimed as a source of beauty and power. The lighting is cinematic, elevating images into monuments of personal freedom.

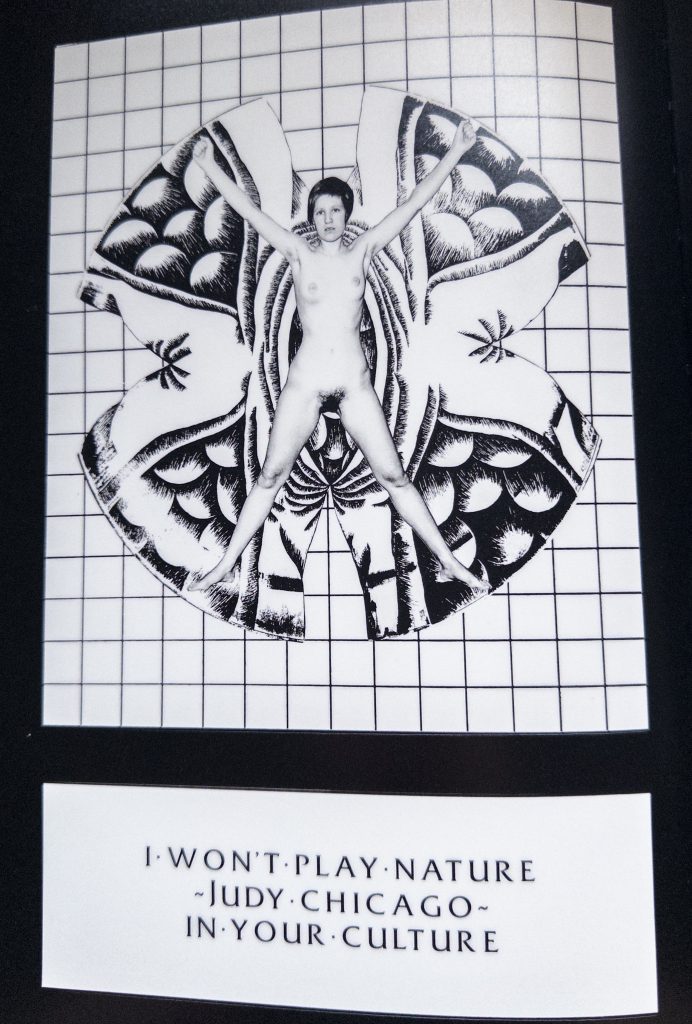

What makes Boffin’s methodology, so electrifying is her clear, intellectual strategy, best articulated by the title of her key series, The Knight’s Move. She understood that realism had failed the queer community, often just reproducing images of suffering. Her solution, as she herself writes, was to go “beyond our impoverished archives and current heroines to create new icons.”

The Knight’s Move metaphor, the chess piece’s signature move of stepping to the side as part of a forward advance, is genius. It becomes a metaphor for the queer community’s need to transgress norms and embrace “transgressive fantasies” to gain ground. Boffin advocates for placing marginalized figures into the great heterosexual narratives of courtly love and heroism, effectively reclaiming those narratives and making them their own.

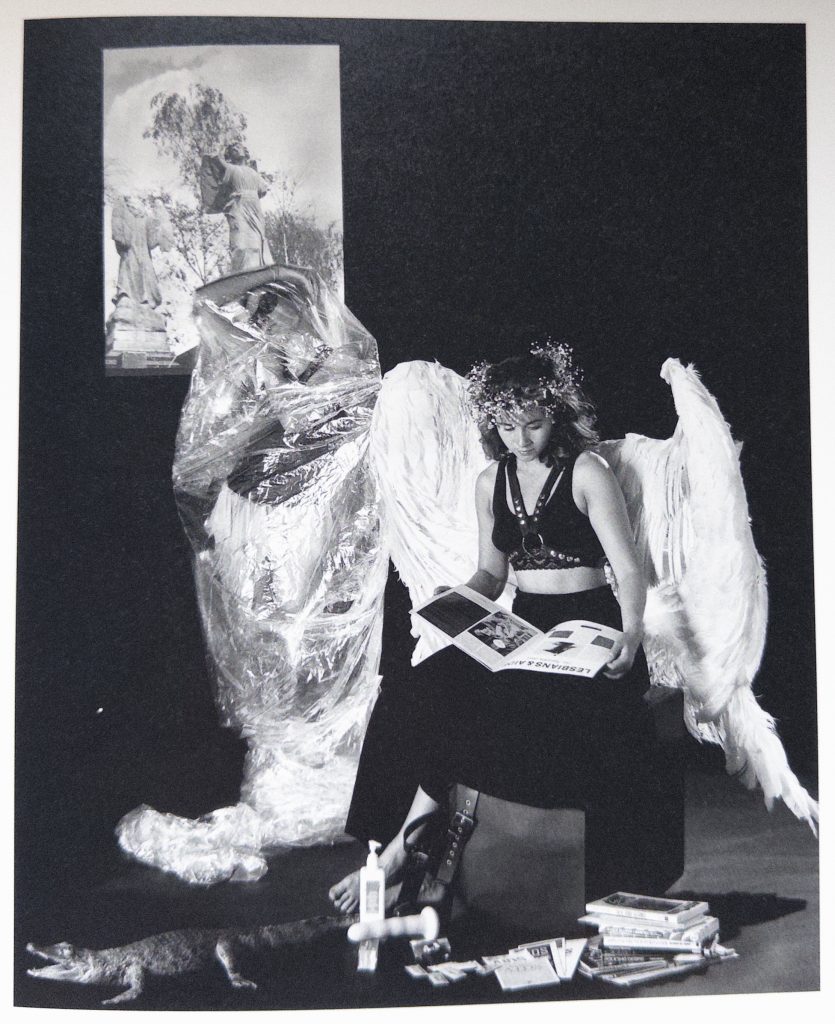

Images from this series visually embody this strategy. The Winged Figure in Harness is all about transformation. I am drawn to the tension between flight and restraint, and this image nails it. The minimal clothing, the wings, the harness, it’s a powerful visual metaphor for freedom constrained by external forces. The deliberate vulnerability of the partially undressed figure, poised heroically, is an electrifying visual assertion that the fight is not just external, but intensely personal, making the body both a target and a monument to queer resilience.

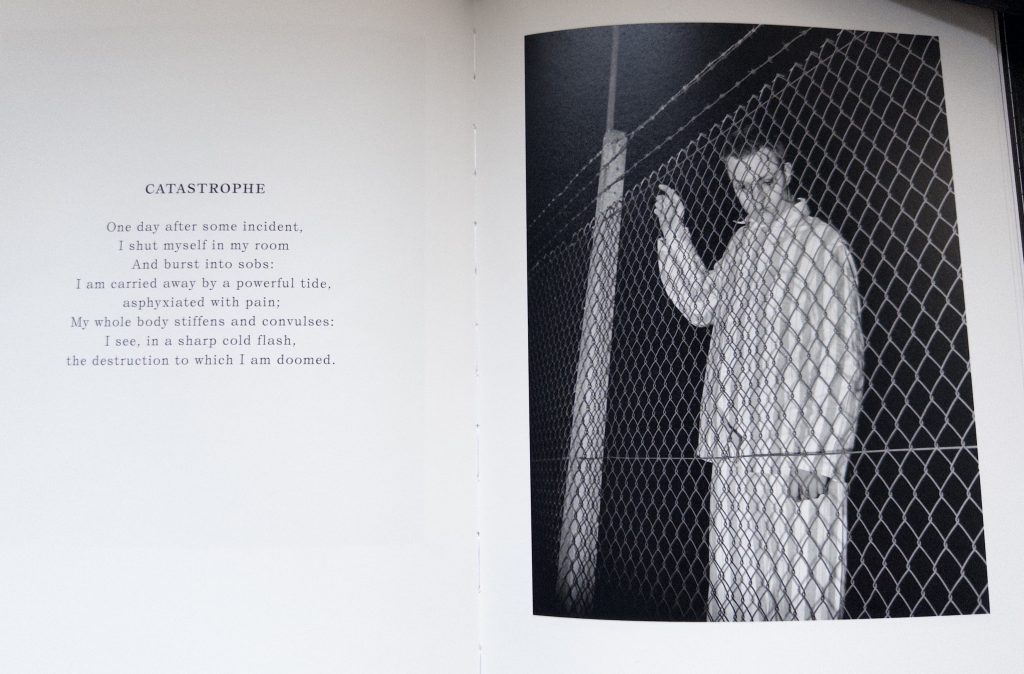

Boffin’s staging often uses the surrounding environment to articulate the societal structures that confine her subjects.

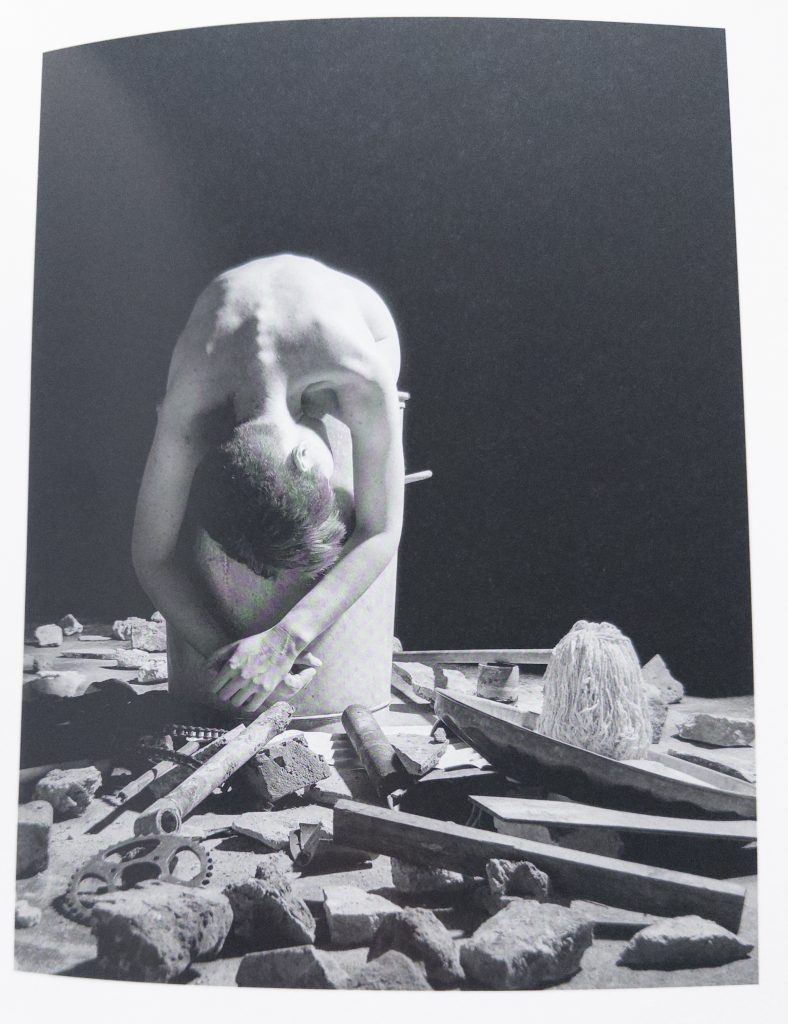

The image of the Nude Figure Bent Over Barrel with Tools is pure tension. The pose is almost sculptural, vulnerable yet defiant. The scattered tools and debris suggest labour, destruction, or perhaps reconstruction. Then, there is the image of the figure partially obscured by cold, angular, geometric scaffolding, which I find conceptually electrifying. The rigid lines perfectly represent the societal structures, the institutional shame, and the limiting definitions that Boffin is battling. The human form is stifled and fragmented by these rules, capturing the profound struggle for visibility and identity against a cold, architectural world, a perfect illustration of the structural failure of a society that refused to protect its citizens.

This structural critique is masterfully balanced by the raw, visceral emotion of the interior life, the Black and White carry the raw, melancholic drama of a theatrical rehearsal. Boffin uses the artificiality of camp and high contrast not to obscure the truth, but to reveal a deeper truth, that sometimes, only performance can articulate the poignant weight of being judged, and the necessary vulnerability required to live an authentic life.

Boffin’s genius is in how she weaves these high stakes political narratives into the surreal, poetic language of fantasy, which resonates deeply with my own aesthetic.

The image of the Angel with Wings, dildo, and Alligator is a collision of fantasy and domestic chaos, exactly the kind of layered surrealism I love. The angelic figure, serene amid scattered objects like a dildo, is like a dreamscape built from memory and adult longing. The juxtaposition of sacred and mundane speaks to evoke emotional dissonance. I love how this image invites narrative speculation without offering resolution.

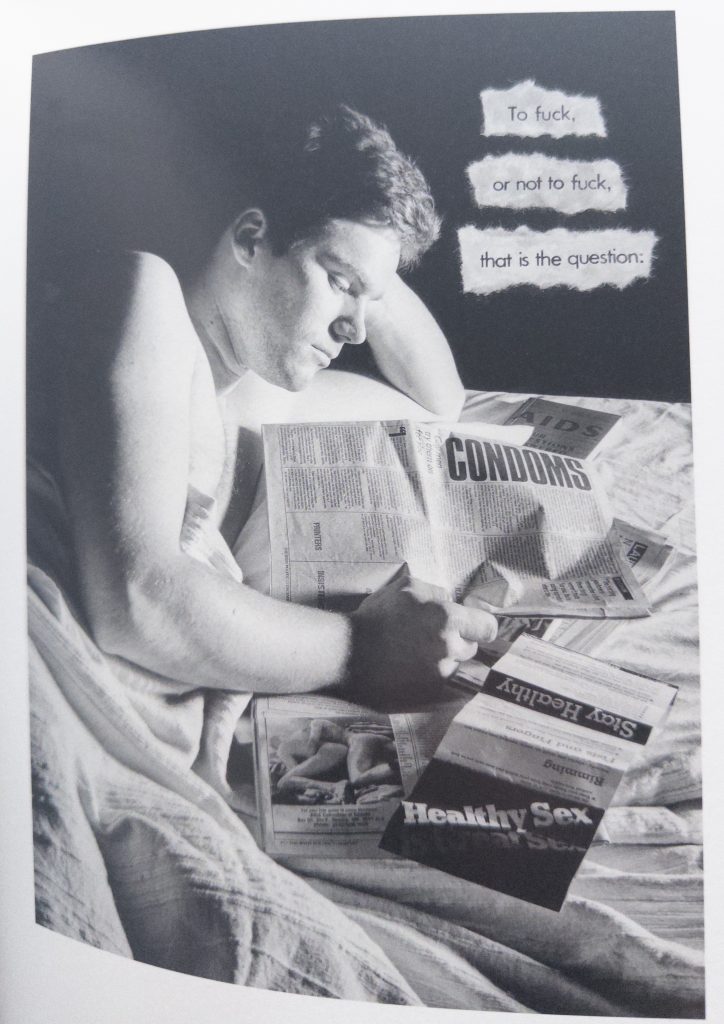

This same poetic sensibility guides the literary text pairings. The spread, “To fuck, or not to fuck…”, is a slap of sexual agency. The Shakespearean twist on choice, paired with the raw vulnerability of reading about sexual health in bed, feels both intimate and confrontational. The layering of text, gesture, and publication titles creates a kind of visual essay. It’s not just about sex; it’s about choice, consequence, and the quiet rituals of self-education.

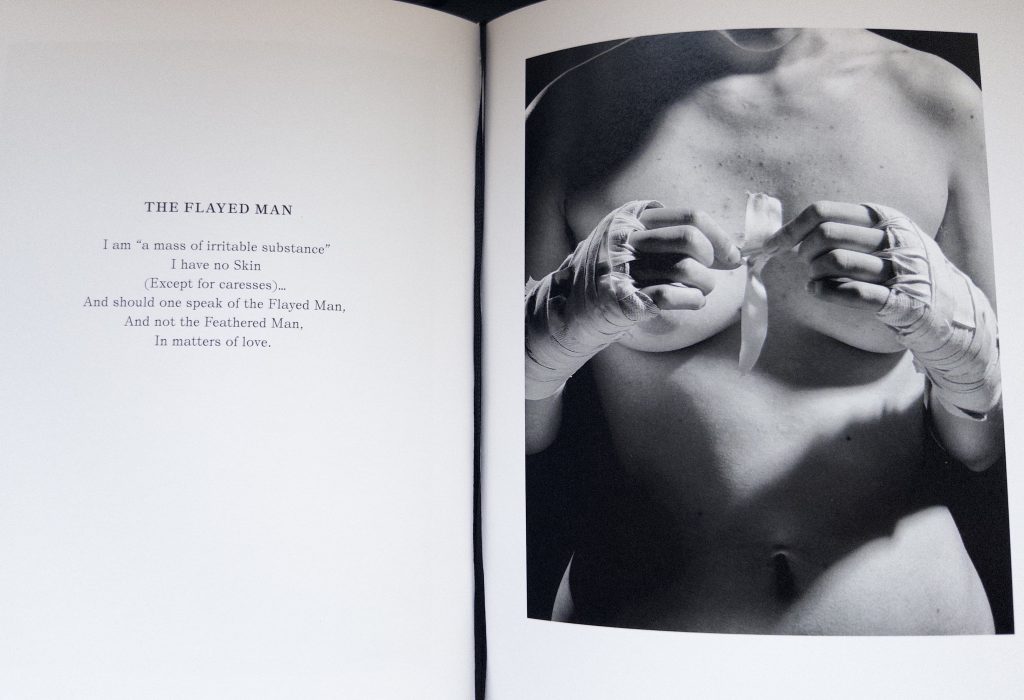

“The Flayed Man” Poem and wrapped hands like a boxer is haunting. The poem’s line, “I have no Skin (Except for caresses)”, feels like something written in a conceptual journal. The photograph, with its hands and exposed chest, evokes themes of healing, intimacy, and emotional rawness. The pairing of text and image here is masterful.

To reiterate, Tessa Boffin is not a retrospective you simply buy and shelve; it is a crafted document of a revolution fought on the stage and with the camera. It is a book that proves the most enduring, most important protest is often found not in the streets, but in the unflinching, visible reclamation of one’s own body and story. It compels us to remember that the right to fantasy, the right to pleasure, and the right to be seen are essential human rights from an artist taking long before her time.

Regards

Alex