I first stumbled upon the work of David Hoffman last month. I was reading an interview with him on the Socialist Worker website, and I was at once taken by his photograph of the Women’s Peace Camp at Greenham Common from 1982. I loved it so much that I featured it as one of my five favourite images in my latest newsletter. This photograph is more than a historical document, it’s a raw and unflinching portrayal of vulnerability and resistance that connects deeply to my own fascination with the societal undercurrents and the stories of marginalised communities. What pulls me into this frame is Hoffman’s masterful use of colour and composition. The sea of protestors, clad in vibrant orange and red rain gear, creates a stunning, almost defiant splash of humanity against the sombre backdrop of the sky and the dark, oppressive uniforms of the police. There’s a breathtaking visual pull between chaos and solidarity, where the saturated hues amplify the fragility of the human condition against authority. It’s a powerful philosophical meditation on the nature of protest and the quiet power of belonging. This unflinching portrayal of vulnerability clashing with authority, with its poignant undercurrent on themes of belonging and the human cost of conflict, left me questioning how we confront power’s impermanence in an unequal world. Hoffman’s dynamic framing and saturated hues showcase a keen process for capturing emotional intensity, inspiring admiration for photography’s power to humanise struggle and ignite contemplation on our shared fragility.

I put it my newsletter: –

“This image is a poignant colour capture from David Hoffman, taken in 1982 at the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp. This photograph isn’t just a historical document, it’s a raw and unflinching portrayal of vulnerability and resistance that connects deeply to my own fascination with societal undercurrents and the stories of marginalised communities.

What pulls me into this frame is the masterful use of colour and composition. The sea of protestors, clad in vibrant orange and red rain gear, creates a stunning, almost defiant splash of humanity against the sombre backdrop of the sky and the dark, oppressive uniforms of the police. It’s a breathtaking visual pull between chaos and solidarity, where the saturated hues amplify the fragility of the human condition against authority. It’s a powerful philosophical meditation on the nature of protest and the quiet power of belonging.

This is an unflinching portrayal of vulnerability clashing with authority, a poignant undercurrent on themes of belonging and the human cost of conflict, questioning how we confront power’s impermanence in an unequal world. Hoffman’s dynamic framing and saturated hues showcase a keen process for capturing emotional intensity, inspiring admiration for photography’s power to humanise struggle and ignite contemplation on our shared fragility.”

Do I agree with every single protest and march that happens across the UK and further afield? Hell no, do I believe they should all be allowed to peaceful protest? absolutely.

This visceral connection, this understanding of the power of protest, is deeply ingrained in me. I come from a family of socialists on my father’s side. I vividly remember my dad showing me a front page image from the Evening Express of the Aberdeen trade union marching up Union Street to protest the Poll Tax in late 1989 or early 1990. My uncle Tommy, who I am named after for my middle name was front and centre helping to hold the banner up as they marched. My dad had cut it out and kept it, a poignant act of memory since my uncle passed away in the early 90s. My own dad also used to wear CND ban the bomb pins on his jackets. His staunch socialist values rubbed off on me, and I too have a deep belief in social justice and a commitment to standing up for the working class. It feels like the majority of the government and people in power do not have our interests at heart. Whether it’s the implementation of policies that disproportionately affect the poor and vulnerable, the privatisation of public services, or a lack of accountability following economic crises, it’s clear that many are in it for what they can get for themselves and don’t get me started on the career politicians whose dad’s and grandads are all politicians too, in it for a pay packet. This book, in turn, gave me a great deal of happiness seeing people fight for what is right and just, but also anger at how they are being treated. While I do not agree with every single protest that happens, I absolutely believe that they all should be allowed to protest peacefully.

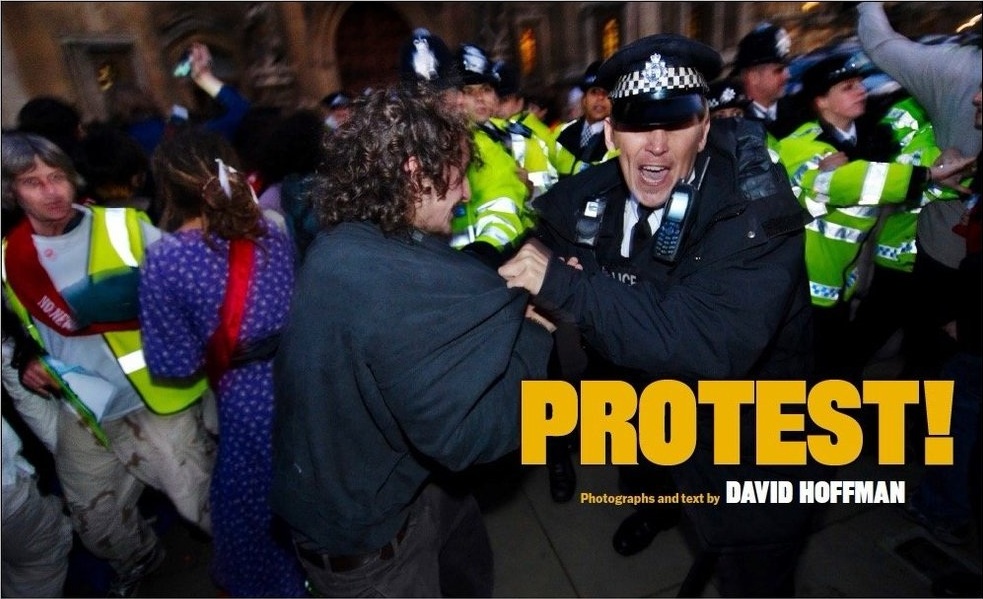

The collection unravels a rich weave of themes that stir my soul, from identity carved in the heat of resistance against state oppression to memory’s poignant grip on moments of defiance. It explores the strength of community uniting marginalised voices, vulnerability exposed in clashes with authority, and the relentless tide of time threatening justice unless we bear witness. The book leaves me to muse on whether art can still ignite transformation in a world teetering on erasure. Hoffman’s immersive approach, forged during his squatting years in Whitechapel from 1973 to 1984, pulses through each frame, his camera a sentinel amid turmoil. Image and Reality’s exceptional presentation lifts the hardback’s 200 page landscape form, its tactile cover and lively sequenced spreads a testament to curatorial brilliance that breathes purpose into the raw energy of protest. I wince when I think about the scratched originals and gruelling proofs he must have endured, a process as taxing as my own darkroom battles where light unveils truth, I have already recommended it to several people.

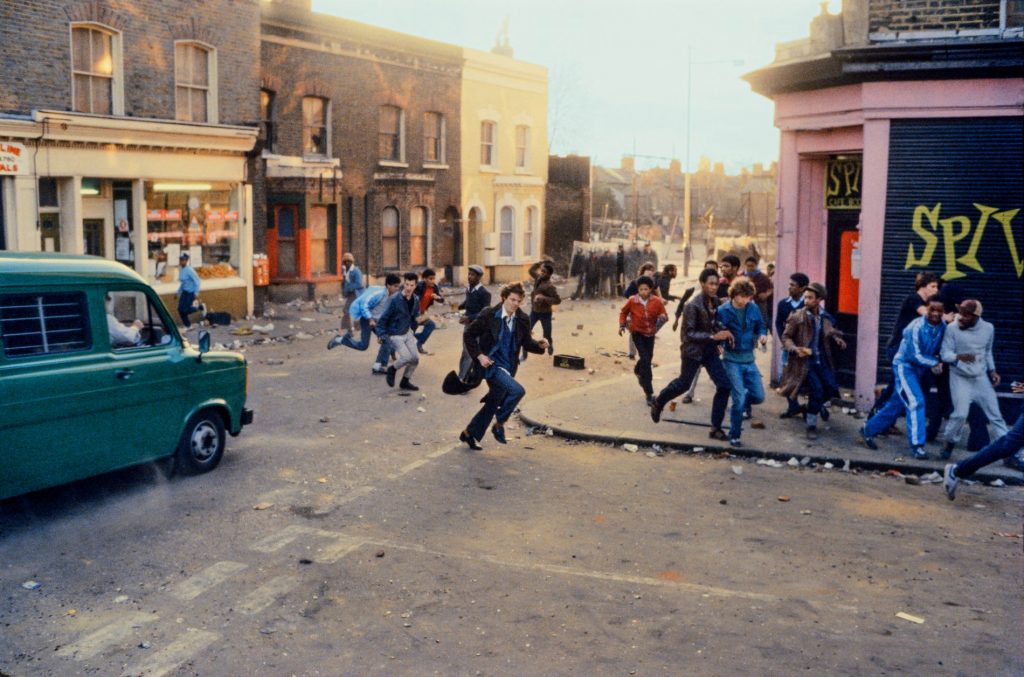

As I delve deeper into the book, the images continue. The Brixton riots shot from 1981 fills me with an unsettling urgency. I see people sprinting down a debris littered street under a hazy sun, their frantic forms blurring against the muted browns and greys of terraced houses and shattered shop fronts, the composition isolating their desperate motion against a chaotic backdrop. The warm, diffused light casts long shadows that heighten the haunting desperation, drawing my eye to a youth glancing back, his expression a silent plea. It leaves me to wonder about the silenced stories behind those fleeing figures and how Hoffman’s dispassionate lens, with its stark framing, exposes the human toll without flinching.

Another spread transports me to the 2010 student fees protest. A vibrant cluster of students perches atop a graffiti scarred bus stop. It’s a busy image at first glance, with one youth in a traffic cone hat gesturing wildly amid signs decrying cuts. Their eclectic attire—bright scarves and jackets—pops against the autumn leaves of the trees’ warm oranges and yellows, and the composition’s angled view captures their exuberant poses in a dynamic arc that evokes profound joy in youthful rebellion. The bold white, red and gold graffiti frames the scene with urban grit, drawing attention to their defiance.

The 1990 Poll Tax riot at Trafalgar Square thunders with incisive fury. I see mounted police charging over fallen protestors, their batons raised amid debris and a blurred sea of bodies. The square’s iconic backdrop is twisted into a battlefield with the low angle shot amplifying the horses’ towering menace against the grey stone and scattered litter. The stark black and white palette intensifies the violence, contrasting the police’s dark silhouettes with the chaotic movement below, igniting my anger at orchestrated oppression. It mirrors the Evening Express image of Uncle Tommy’s march that my dad treasured. It fosters a curiosity about the crushed dreams beneath and vulnerability’s cost in collective fury, a sobering reminder of how such moments challenge social inequality’s quiet weight and still sicken most of Scotland to this day.

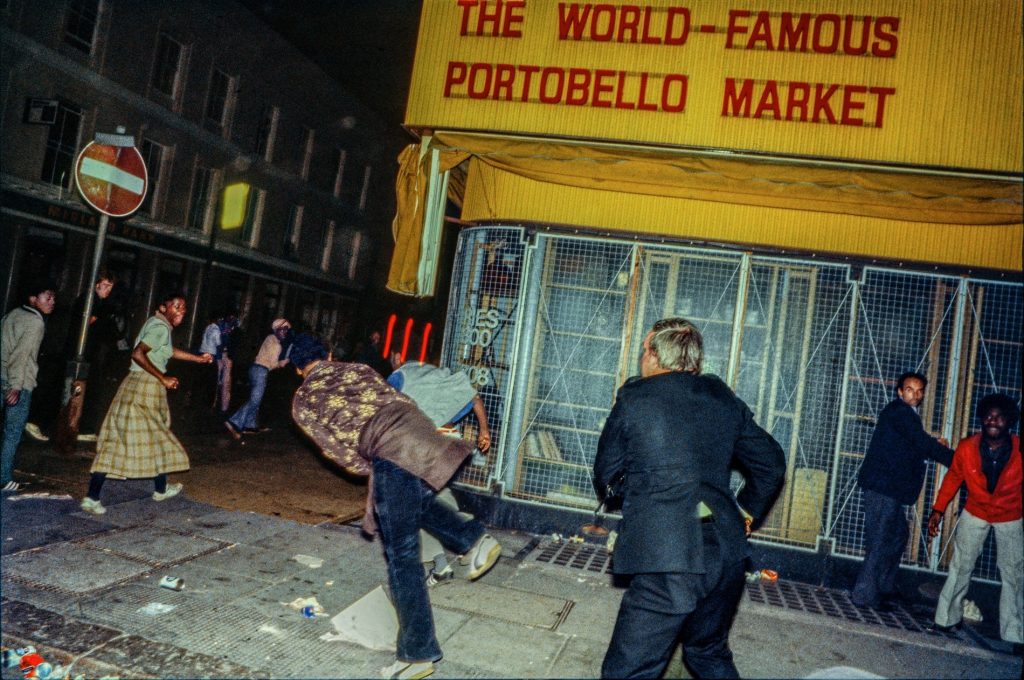

A nocturnal Notting Hill Carnival clash from 1979 unfolds with frantic energy. Figures scatter from a shuttered market under dim streetlights, one tumbling forward as if he has just thrown something amid graffiti and debris. The composition spotlights his mid fall motion against the market’s muted blues and yellows. The low contrast lighting casts eerie shadows, enhancing the cultural tensions that haunt me with thoughts of overlooked communities clashing against systemic bias. It makes me wonder about the rhythms disrupted and authenticity’s fight for space in a divided city, the frame’s raw framing leaving a lasting impression of impermanence.

These glimpses from Hoffman’s lens reaffirm photography’s power to immortalise the heartbeat of passions that unite us.

In a time when protest is often vilified or dismissed, Hoffman’s work feels more vital than ever. The right to challenge injustice, to speak truth to power, and to gather in solidarity is not a luxury, it’s a cornerstone of any functioning democracy. Whether it’s climate activists, striking workers, or communities resisting systemic racism, the images in Protest! remind us that dissent is not disorder, it’s a demand for dignity. These photographs are not relics of the past, but mirrors held up to the present, urging us to stay awake, stay vocal, and stay human.

We all deserve a basic standard of living, access to shelter, healthcare, education, and safety, and we all deserve the freedom to disagree, to question, and to protest peacefully when those rights are threatened. Hoffman’s lens doesn’t just document resistance, it honours it. Protest! is a call to remember that behind every placard is a person, behind every march a movement, and behind every image a story worth telling. It’s a book that doesn’t just sit on the shelf, it stands up.

Protest! rekindles my love for art that pulses with our defiant heartbeat. Art with a purpose is great. The book is a testament to Hoffman’s vision of showing communities as they are, honest, imperfect, and unadorned.

Regards

Alex