Welcome to the first chapter of my Historical Movements in Photography ramble, a journey I kicked off in “Historical Movements in Photography: A Timeline of Artistic Evolution”. Let’s step back to a time when photography wasn’t just a cold click but a dreamy defiance of reality itself. Pictorialism, blooming from 1885 to 1915, wasn’t some fussy style, it was a battle cry.

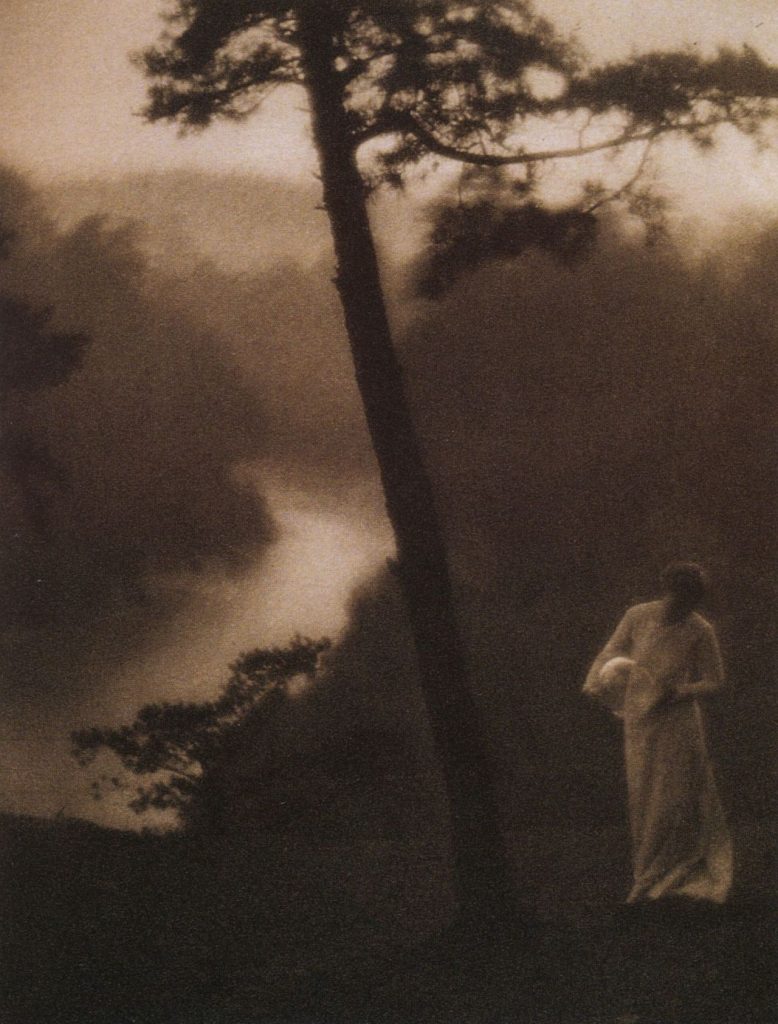

Photographers turned their lenses into brushes, smudging sharp edges with soft focus, textured prints, and moody compositions. In an era doubting a camera’s soul, they proved it could sing, not just record.

Picture the late 19th century: the Industrial Revolution’s clanging machines drowning out the old ways. Photography, sharp and exact, felt more science than art, lenses honed to mirror reality like a cold Aberdeen dawn. Early pioneers obsessed over clarity, but as cameras spread, a restless few pushed back. Pictorialists didn’t care for pinpoint truth; they craved feeling. To them, a photo’s worth lay in its shiver of emotion, not its slavish detail, a rebellion I’d have cheered, growing up with comics where every panel pulsed with mood.

At its heart, Pictorialism was about crafting, not capturing. These folk wielded soft-focus lenses, hand-coated papers, and tricks like gum bichromate or platinum printing, alchemy in the darkroom. They blurred the line between photo and painting, chasing a haze that felt alive. It’s the kind of grit I admire, like thistles clawing through Aberdeen’s granite, a stubborn bid to make something raw and real sing with soul.

Alfred Stieglitz stands tall here, an American firebrand who fought for photography’s place in the art world. Through Camera Work and his Photo-Secession crew, he gave Pictorialists a voice. His The Terminal (1893), all misty streets and smudged edges, wraps you in its atmosphere like fog off the North Sea. He was a tastemaker, a dreamer, even if he later drifted to sharper shores. Stieglitz’s prints feel like stories, not snapshots, and that’s a thread I chase in my own frames.

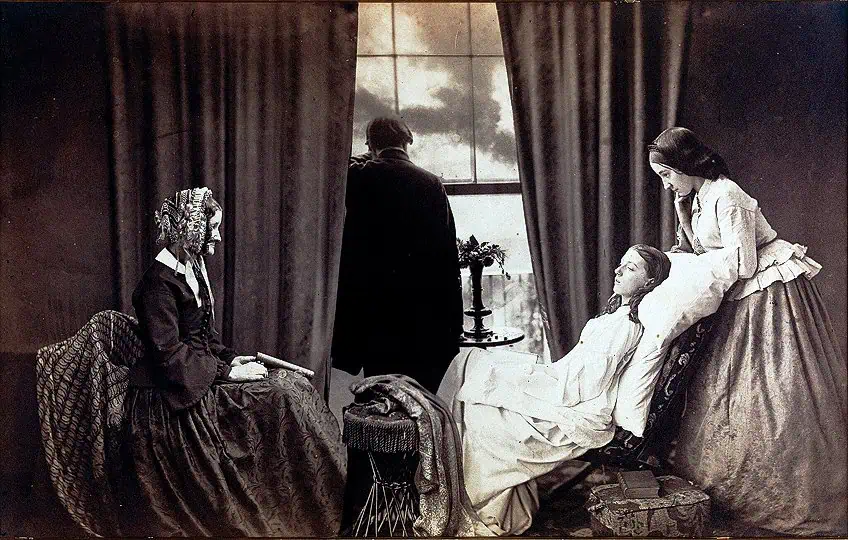

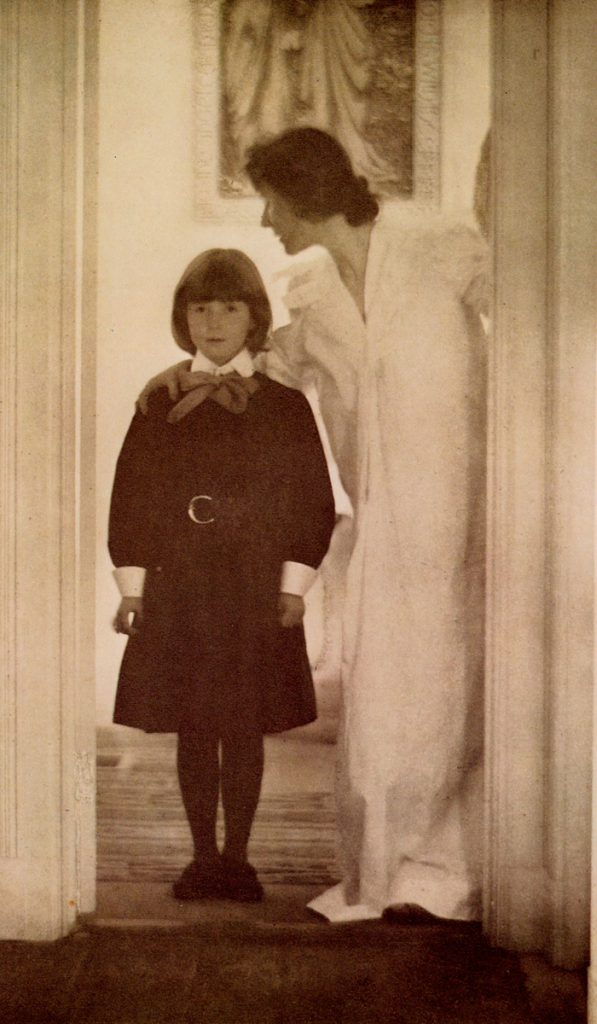

Across the water, Julia Margaret Cameron was weaving her own magic. Her portraits, literary faces, mythic scenes, shunned crispness for a soft, ethereal glow. Critics sniffed at her “imperfections,” but to me, that’s the beauty: flaws that breathe. Her work’s a quiet echo of my Dali print from childhood, less about precision, more about what lingers in the mind’s eye. Cameron made photography personal, a gift she handed down through every misty frame.

Painting was Pictorialism’s muse, Impressionist light, Pre-Raphaelite romance. Portraits glowed with allegory, landscapes sighed with longing, all crafted to stir the heart, not just map the world. It’s like flipping through an old comic, each image a panel, tugging you into its tale. Salons and clubs, like Britain’s Linked Ring (1892) or Stieglitz’s Photo-Secession, fanned the flames, giving space to experiment and shout that photography wasn’t just for scientists.

Today, Pictorialism feels like a weathered photobook on my shelf, a chapter of resistance. Its misty hills, dreamy faces, and painstaking prints defied the camera’s cold heart, proving beauty could bloom through a lens. Modern snaps lean sharp, but you’ll spot its ghost in fine art’s textures and moods, tools I’ve tinkered with myself, chasing that same shiver. It was photography’s comic-book era bold, expressive, all soul over fact. Its spirit lingers in every frame that dares to feel.

Regards,

Alex