As a 40 something dad running this site and working full time, I find that a good photobook can often resonate in a way I didn’t expect, cutting through the daily chaos of my life and speaking to a deeper truth. Joseph-Philippe Bevillard’s Mincéirs, published by Skeleton Key Press, is one of those books. With my oldest living her best adult life post Uni down in Glasgow, my middle child with severe autism and Tourette’s requiring full-time care from my wife and me, and my youngest with autism and ADHD home educated by us, these images strike a chord that reverberates through my busy life. I see reflections of a quiet resilience and a fierce sense of identity in every frame, mirroring the strength I see in my sons daily as they navigate their worlds with a mix of pride and challenge. The book, a culmination of over a decade of work, offers an unflinching yet compassionate window into the lives of Irish Travellers, also known as Mincéirs. It is a masterclass in humanistic photography, a subject that connects so deeply to my love for storytelling on this site, where I dissect photobooks for their emotional depth. This book does so with a raw honesty, free from pity or exoticism, which is a rare and precious thing.

I posted this to Instagram after the first read, I have read it three times now before writing all this.

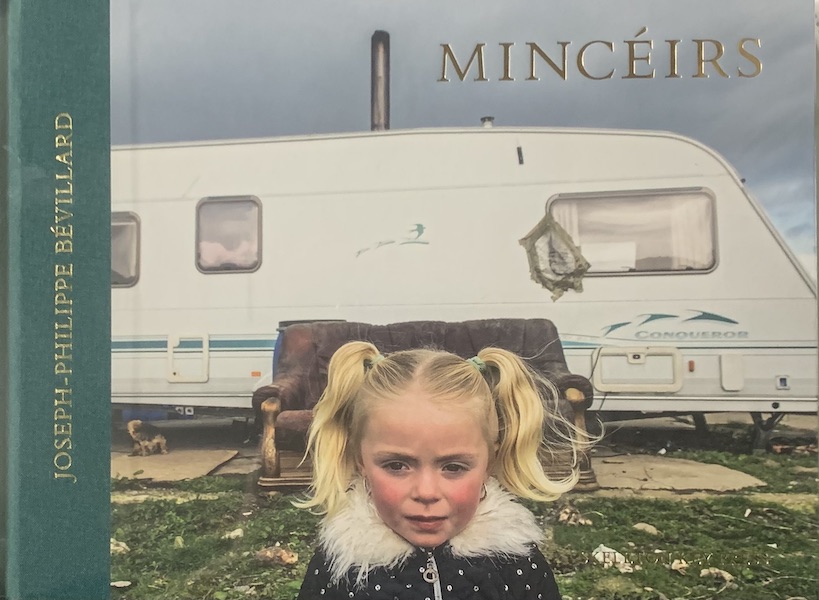

Bevillard’s journey began in 2009, a few years after he moved to Ireland from the United States. His curiosity about the Traveller community, first sparked by a professor long before he even arrived, led him to embark on a pure documentary immersion. This wasn’t a quick project but a slow, patient process of earning trust within the community, capturing unposed moments rather than staging them. That commitment to authentic connection is palpable on every one of the book’s 144 pages. The physical object itself screams quality, a sturdy hardcover that feels substantial in your hands. Skeleton Key Press has presented a beautifully crafted volume, with a smooth paper stock that allows the saturated colours to pop against the often grey Irish backdrops. This isn’t a book of black and white minimalism. Bevillard’s use of vibrant hues to contrast the drab caravans and makeshift halting sites makes the humanity shine through in a way that is almost cinematic.

The photographs themselves act as a springboard to explore deeper themes such as identity, community, vulnerability, and resilience. I find myself pausing on a particular image, the one of a young lad I’ve come to think of as ‘The Young Celebrant’. He is perched on a plush, white leather sofa, decked out in a crisp Communion suit, holding a blue balloon emblazoned with “On Your Communion”. The room is a riot of opulence, golden pineapple statues, ornate glass cabinets stuffed with crystal, and creamy curtains framing a glimpse of caravan life outside. The light pours in soft but deliberate, casting gentle shadows that highlight the boy’s solemn face. There is a quiet pride there, mixed with a kid’s uncertainty. Bevillard nails the contrast in this shot. The lavish interior clashes with the rugged Traveller halting site just beyond, telling a story of celebration amid a transient existence. The composition’s tight, centring the boy like a lone figure on a grand stage, with those balloons adding a playful yet poignant touch. It is a moment of joy wrapped in resilience, a feeling I understand all too well.

Here is a shot that tugs at the heartstrings, a family of eight siblings lined up in front of a weathered caravan, their mix of expressions and outfits painting a vivid portrait. The light’s diffused by a cloudy sky, softening the edges of the scene, with the caravan’s faded white standing stark against the green overgrowth at its base. The adults, a bare-chested man with a cap and a woman in a floral top, flank the kids, who range from a toddler in a white onesie to a girl in a striking red dress with fringed sleeves. The kids’ poses are natural, some shy, some bold, their clothes a patchwork of styles, denim shorts, floral dresses, and sandals, reflecting a life on the move. The composition’s wide, framing the family against the caravan like a stage, with the rough terrain adding texture to the narrative. This resonates with me as a parent navigating family dynamics with neurodiverse kids, each face a story of strength and unity. It is the kind of human tapestry I would love to explore further on Viewfinder Chronicles, playing with depth and light to capture similar raw connections.

This one leaps off the screen, a young lass with a wild mop of red hair, her freckled face lit up with a cheeky, gap-toothed grin, standing in front of a red van with a ladder racked on its side. The light’s soft and overcast, casting a gentle glow that dances across her features, while the van’s bold hue pops against the muted grey of the road and nearby houses. She is dressed in a simple blue shirt, a contrast to the chaotic energy of her expression, those missing teeth and squinted eyes tell a story of pure, un-filtered joy. The background blurs with kids in motion, adding a sense of lively community, while the Irish license plate (“BÁILE ÁTHA CLIATH”) hints at a specific place, grounding the moment. The candid capture feels akin to Bevillard’s immersive style, pulling me into a narrative of childhood freedom. As a dad, I see echoes of my own kids’ unguarded moments, those rare, bright bursts amid our structured days, making me itch to experiment with similar natural light on my site.

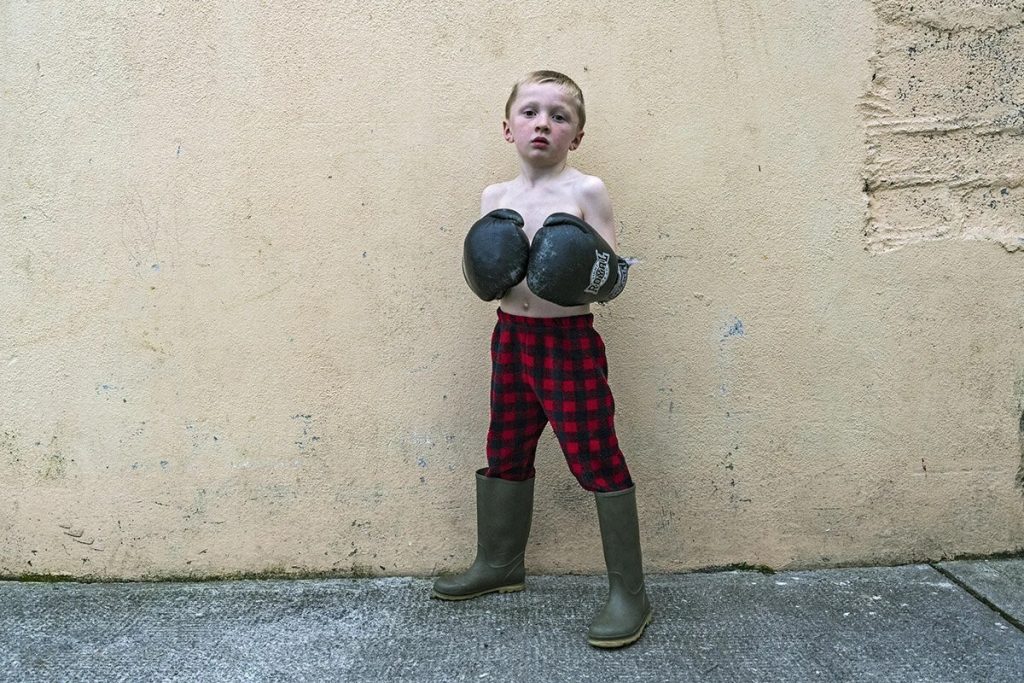

What makes this book so powerful is its compassionate nature and perceptive eye. As Peggy Sue Amison states in her insightful essay, Bevillard’s close personal understanding of what it is like to be considered different resonates in each image. His sensitive and beautifully seen moments help to break down stereotypes and work towards dispelling past misunderstandings. This is a particularly unique tie in for me. As a dad to kids on the spectrum, I see parallels in celebrating resilience. The Travellers facing discrimination is much like navigating neurodiversity in a “settled” society, and this book serves as an eye opener for those quick to judge outsiders. The work pushes back with empathy, using vibrant colours to highlight joy amid hardship, from kids playing to elders in quiet dignity, it is hard to not feel sorry for the kids somewhat but they wouldn’t know any other world I imagine.

Bevillard’s work is an immersion, in bright colours against a generally grey sky, in a community he has accepted with heart. It reminds me of the importance of patience and connection in all artistry, cherishing the stories closest to home. The book is a reminder that the best documentary photography comes from genuine care for its subjects. It is a profound philosophical exploration of what it means to be human, and to be part of a community. The book is more than a collection of photographs, it is a testament to the power of a compassionate lens.

At the end of the day, Mincéirs is a masterclass in humanistic photography, offering a profound reflection on resilience and the power of empathy. It is a book that effortlessly knocks down barriers, providing a clear and authentic window into a community often misunderstood, and reminding us that true artistry lies in genuine connection and care.

Regards

Alex