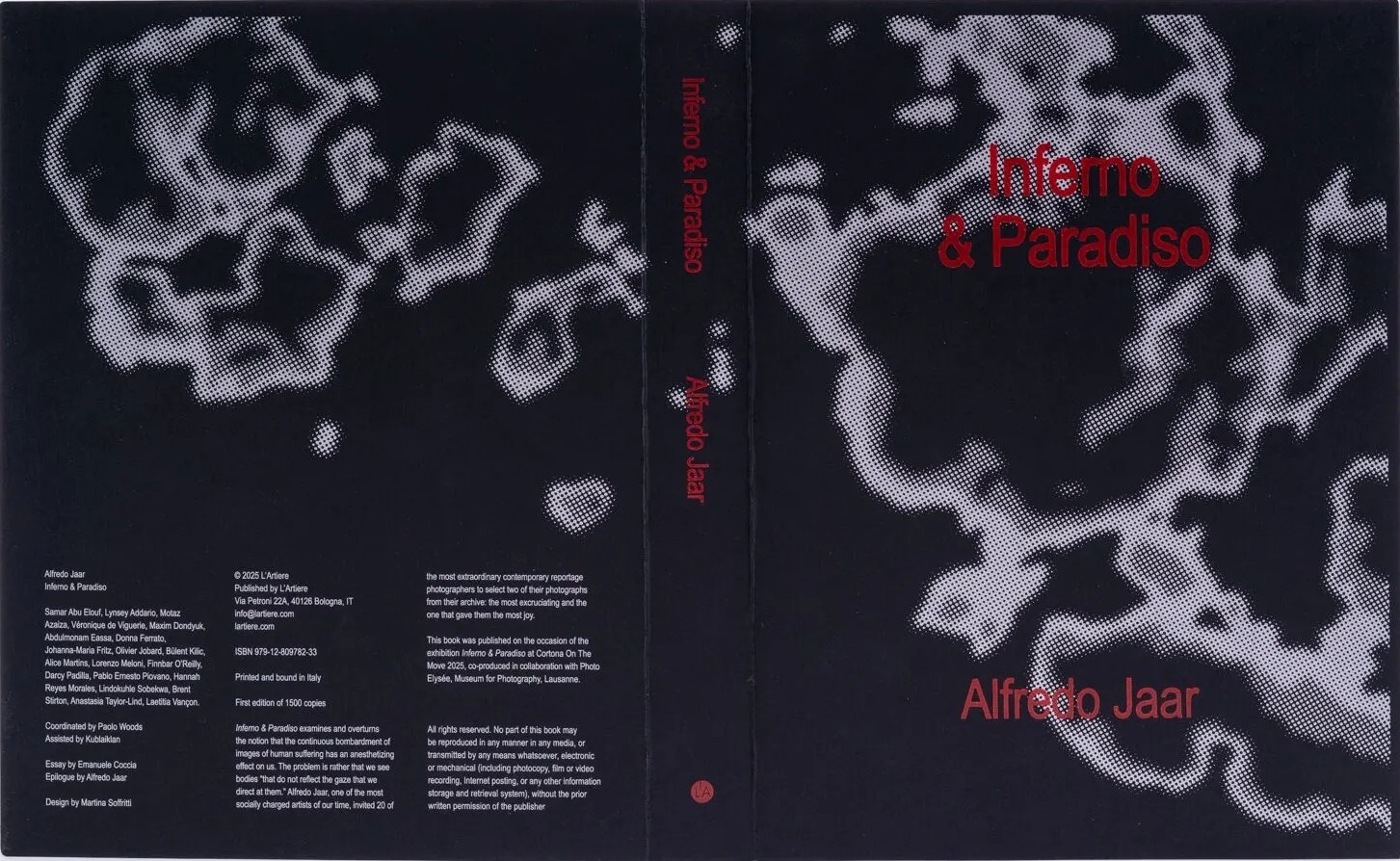

There are some photobooks that you read, and then there are others that read you. They arrive in your hands not as curated collections of beautiful prints, but as an unflinching challenge to your very soul, forcing you to confront the ethical and emotional cost of simply looking at the world today. Alfredo Jaar’s magnificent, devastating, and utterly essential work, Inferno & Paradiso, published by L’Artiere Books, is emphatically the latter.

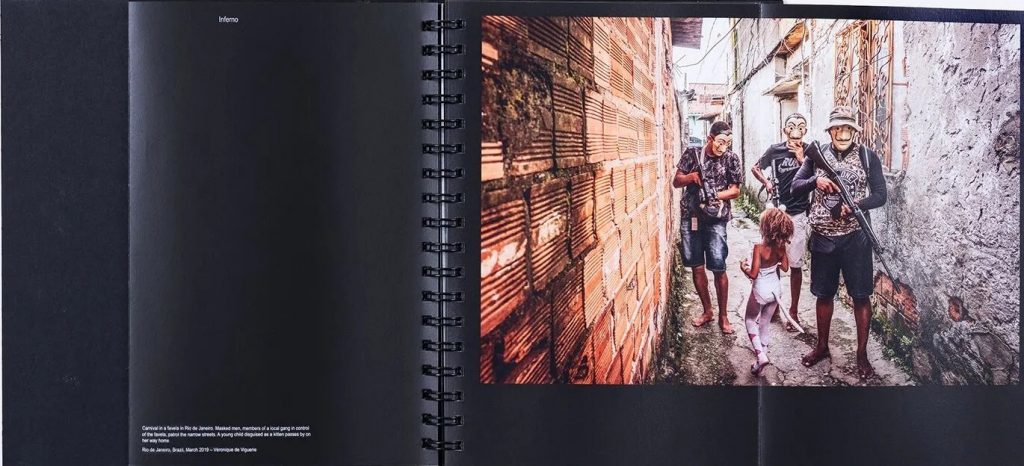

Carnival in a favela in Rio de Janeiro. Masked men, members of a local gang in control

of the favela, patrol the narrow streets. A young child disguised as a kitten passes by on

her way home.

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, March 2019 – Véronique De Viguerie

This is why it sits atop my reading pile right now, an object of both intense dread and profound necessity. My own small project, that intimate, vulnerable exercise of trying to photograph my wife’s eyes and truly see the person I share my life with, is ultimately about finding an essential, singular truth amidst overwhelming detail. Jaar’s project operates on a far grander, global scale, but asks the same core question, when the world is fractured and the light is dim, where does the truth reside, and how much of ourselves are we willing to commit to finding it?

The genesis of Inferno & Paradiso is rooted in an experience of human history so horrific it broke the artist, Jaar’s visit to Rwanda in 1994, just after the genocide. He arrived to find not just bodies, but a silence so thick it was touchable, an absence of meaning that led him to a complete state of despair and emotional collapse. The experience forced him to grapple with the ultimate failure of art, the inability of any image to truly convey the scale of such atrocity. Yet, it led to an even stronger conviction that the moral failure of not looking was the most despicable act of all.

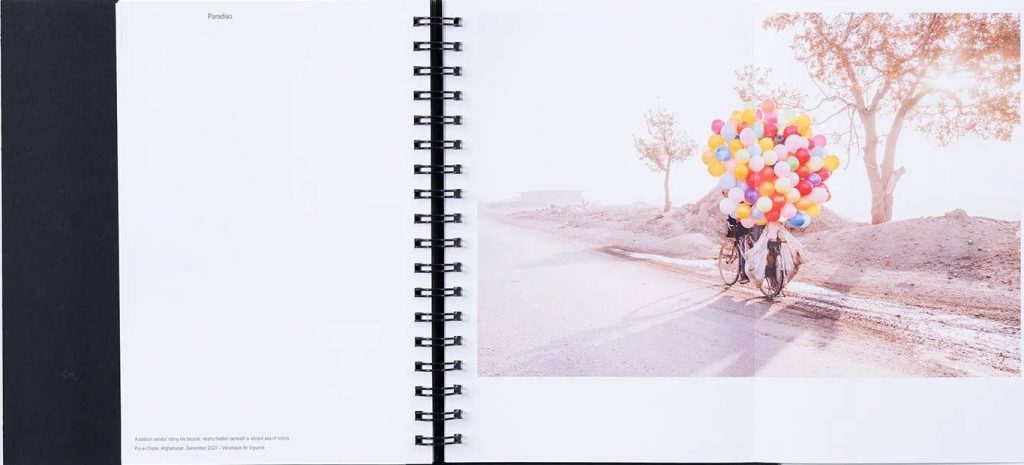

A balloon vendor riding his bicycle, nearly hidden beneath a vibrant sea of colors.

Pul-e-Charki, Afghanistan, December 2023 – Véronique De Viguerie

This realisation became the engine of the book. Jaar conceived an artistic device to address the anaesthetizing effect of constant media bombardment, the visual noise that causes us to look away, to shrug, to become indifferent. He invited twenty of the world’s most experienced and morally courageous photojournalists to collaborate, asking them to perform a deeply personal, almost purgatorial act of choice from their own archives.

Inferno: The single most harrowing, painful image they had ever taken, the one that still gives them nightmares.

Paradiso: The most joyful, hopeful moment they had ever captured, a small, radical instance of grace that shone through the chaos of their difficult lives.

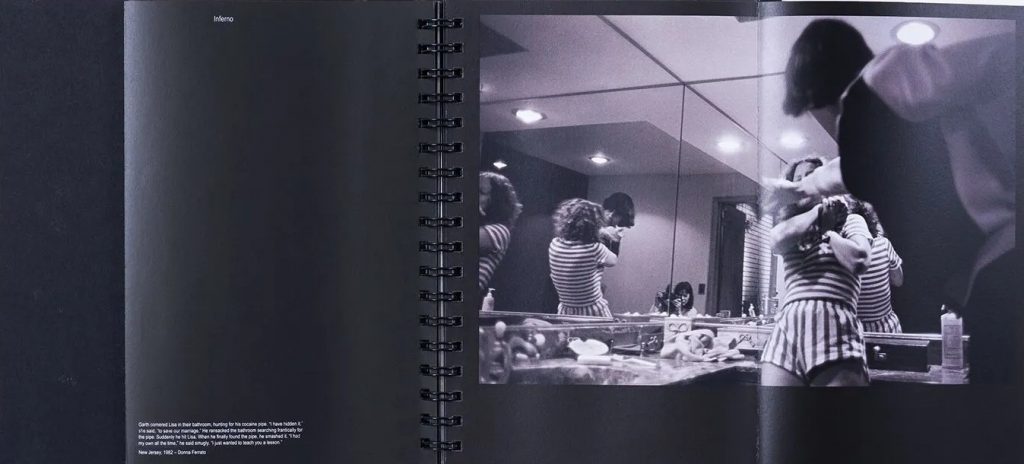

Garth cornered Lisa in their bathroom, hunting for his cocaine pipe. “I have hidden it,”

she said, “to save our marriage.” He ransacked the bathroom searching frantically for

the pipe. Suddenly he hit Lisa. When he finally found the pipe, he smashed it. “I had

my own all the time,” he said smugly. “I just wanted to teach you a lesson.”

New Jersey, 1982 – Donna Ferrato

This deliberate juxtaposition is a visceral, philosophical gut punch. It forces us to hold the weight of the two extremes simultaneously, the darkest expression of human inhumanity and the persistent, elemental possibility of human connection and light. This is not a project that offers comfort or neat answers, it offers the truth of the struggle.

What elevates Inferno & Paradiso beyond a catalogue of dualities is its structural brilliance, what Jaar himself calls the politics of images.

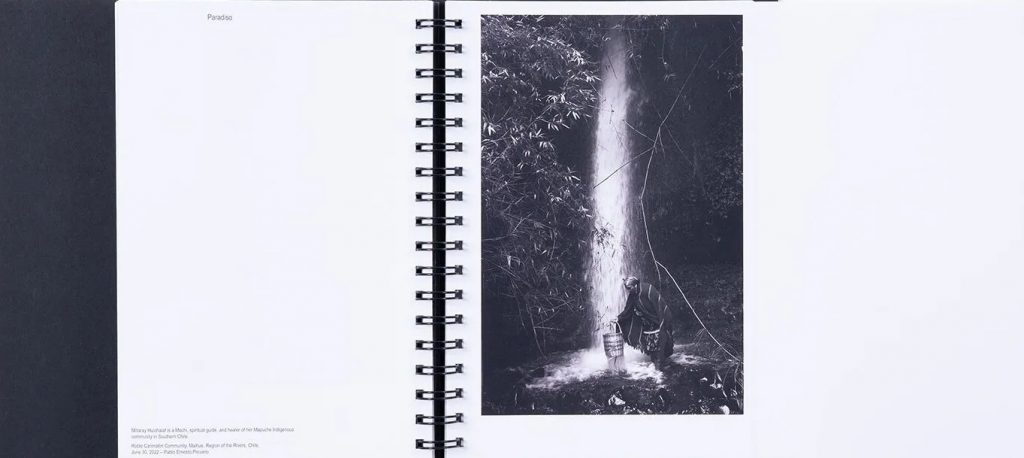

Millaray Huichalaf is a Machi, spiritual guide, and healer of her Mapuche Indigenous

community in Southern Chile.

Roble Carimallin Community, Maihue, Region of the Rivers, Chile,

June 30, 2022 – Pablo Ernesto Piovano

And here is where the project finds its fiercest, most unflinching ethical grounding. Jaar is explicitly challenging indifference. He quotes the philosopher Antonio Gramsci, whose words stand as a thunderous manifesto for this entire project,

“I hate the indifferent. I believe that living means taking sides. Those who really live cannot help being a citizen and a partisan. Indifference and apathy are parasitism, perversion, not life. That is why I hate the indifferent.”

This quote is a poignant commentary on our modern existence. Jaar is screaming at us to stop being “parasites” on the suffering of others and to become active witnesses to the reality of the world. The book, in its very structure, is a tool designed to strip away our armour of apathy and force us to become human again.

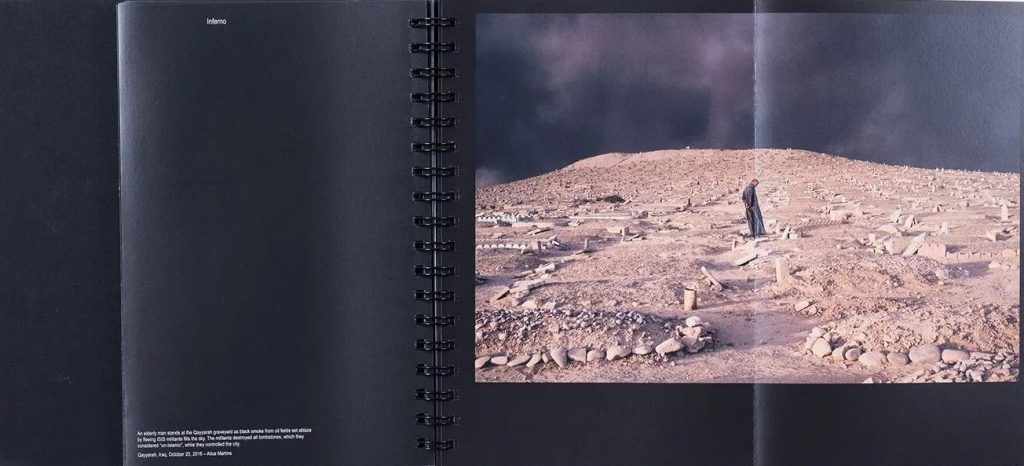

An elderly man stands at the Qayyarah graveyard as black smoke from oil fields set ablaze

by fleeing ISIS militants fills the sky. The militants destroyed all tombstones, which they

considered “un-Islamic”, while they controlled the city.

Qayyarah, Iraq, October 20, 2016 – Alice Martins

Flipping through the images, the stark contrast between the lone figure running across the cracked, desolate earth (Inferno) and the sheer, kinetic joy of children running free down a sunlit hill (Paradiso), is an electrifying, unsettling experience.

You see the visceral horror in the bloodied, uncomfortably close face and the immense socio political weight of children framed against a desolate crisis landscape. But then, you are given the relief of collective humanity in a moment of solidarity, or the quiet, profound connection in the delicate handling of a tiny, fragile bird.

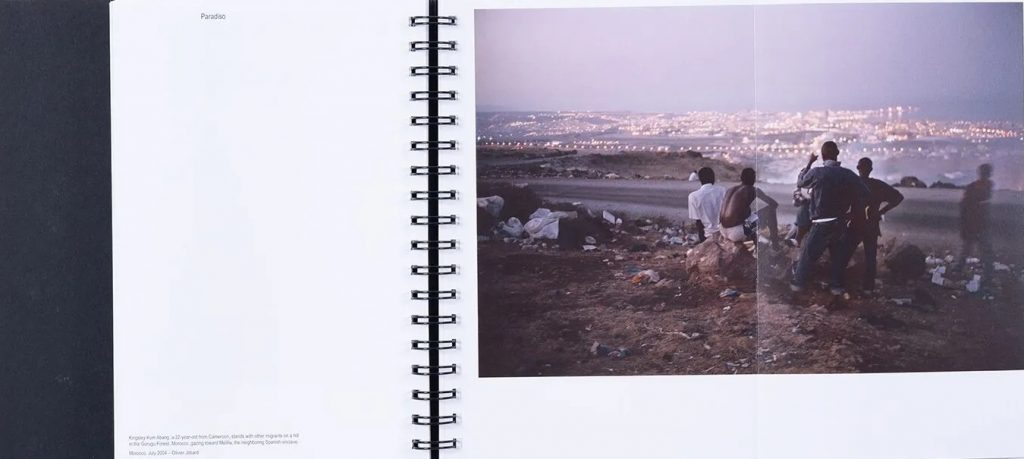

Kingsley Kum Abang, a 22-year-old from Cameroon, stands with other migrants on a hill

in the Gurugu Forest, Morocco, gazing toward Melilla, the neighboring Spanish enclave.

Morocco, July 2004 – Olivier Jobard

The project does not seek a comforting conclusion. It seeks to set up an impossible balance, an ongoing conversation between the two extremes that define our era. It’s a secular pilgrimage through human experience, an acknowledgement that even in the midst of global collapse, a touch, a glance, a colour can reveal a way out. It’s a reminder that beauty, dignity, and solidarity are not just lovely ideas, but essential artistic and political tools.

Perhaps the most compelling and valuable feature of this book, the one that truly brings photography right back to the audience, is its final act. The first edition of the photobook included a card inviting the reader to give their own “Inferno” and “Paradiso” assignments to complete the project.

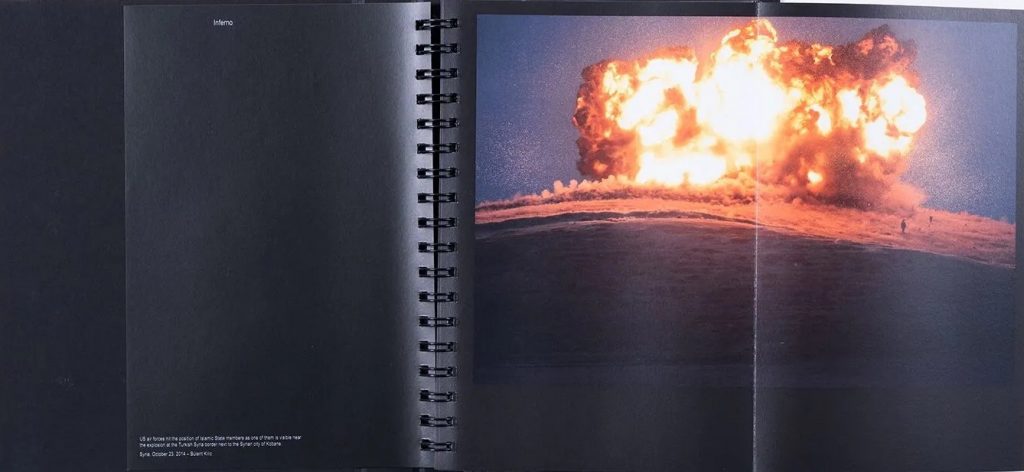

US air forces hit the position of Islamic State (IS) members as one of them is visible near

the explosion at the Turkish Syria border next to the Syrian city of Kobane.

Syria, October 23, 2014 – Bülent Kilic

This is a precious process, a call for involvement that aims for a second volume and a gallery display featuring the audience’s own responses. Jaar is not content with simply presenting his truth, he is inviting a collective self portrait of those who see both atrocity and grace. He transforms the end of the book from a passive conclusion into an open ended, active beginning.

This is the ultimate lesson for all of us struggling with our own work. Whether it’s documenting the enduring granite gleam of a local landmark or trying to capture the truth in a loved one’s eyes, the moment our image creates a flicker of recognition, a challenge, or a connection in another person, the work is complete. Jaar proves that the most powerful art is the art that refuses to let us be spectators, demanding instead that we become active witnesses.

Inferno & Paradiso is not a book you simply buy and shelve, it is a moral test, a desperate cry for us to become human again, and an absolute requirement for anyone who believes that the camera still has the power to change the world. Highly, urgently recommended.

Regards

Alex