I love European Photography Magazine, it is such a deep and thoughtful book that when reading is a truly sobering experience and makes you ask some hard questions about what it means to be a photographer, or an ethical image maker, right now. Given that I have been dabbling into AI art myself and will be adding a page or sub page to the website about it I really enjoyed this issue a lot.

The editor, Andreas Müller-Pohle, whose book `Niépce Recoded` I have already reviewed on the site lays out the unflinching conceptual framework, artificial intelligence, politics, and nature. This isn’t a leisurely tour, it’s a necessary, visceral confrontation with the three epochal shifts defining our reality, one that immediately connects to my own struggle to transition my work from chasing the “decisive moment” to grappling with the melancholic weight of these vast, systemic narratives and trying to find a style, rhythm and identity in my own AI work too.

The first focal theme, Artificial Intelligence, I appreciate that the magazine doesn’t shy away from calling it out, it’s an overriding epochal shift for us image makers, an existential threat to some, a creative challenge to all. What I find electrifying is the magazine’s commitment to the conceptual use of AI, deliberately pushing back against the “onslaught of anecdotal kitsch” that floods every channel. Lionel Bayol-Thémines’s Al Generated is a perfect example of this incisive approach. He rebels against the standard of producing photorealistic images, instead using the free model Craiyon to submit the same history of photography related prompt thousands of times. The goal? To explore how the neural network could be prompted to generate aberrant results, or “visual hallucinations”. It’s a profound and unsettling exploration into AI as a “Gap Filler” that deliberately hunts for the machine’s failure points, creating an index of bias and bugs as its output. Similarly, Phillip Toledano’s We Are at War is historical surrealism at its finest. He acknowledges that AI has rendered history “infinitely elastic,” making everything simultaneously true and false. Toledano uses AI to fill the “empty pocket of history” left by Robert Capa’s lost D Day rolls, demonstrating how utterly convincing invented history can be. The terrifying, arresting question at the core of these projects is unavoidable, if we can rewrite the past with such seamless, false authority, what control do we have over the present?

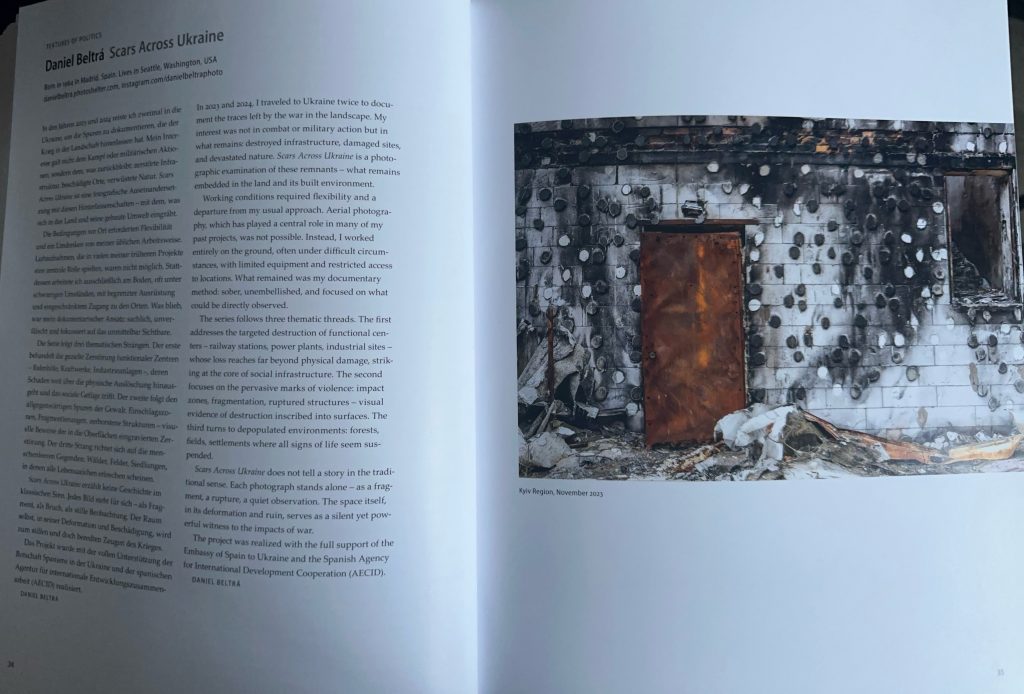

The second focus, Textures of Politics, brings us back down to the raw, physical reality of societal upheavals and conflict zones, forcing us to engage beyond the overwhelming rush of daily events. The four contrasting positions are necessary and poignant. You have the “abstraction of horror in Ukraine” captured in Daniel Beltra’s Scars Across Ukraine, where the scale of destruction is so vast it becomes almost topog=-raphical, forcing a wider, more ethical contemplation of the war’s cost. Mateus Gomes’s Escombros offers a different kind of war, a long-term study of globalization’s effects in Brazil, showing the melancholic residue of economic conflict. Then there’s the direct confrontation with power dynamics, Paul Yeung’s police observations from Hong Kong, Yes Madam, Sorry Ah Sir, and Sean Cham’s personal enactments addressing Singapore’s postcolonial legacy in Eastern Promise. These projects show the human body caught in the machinery of the state, making the abstraction of “politics” something immediately visceral and personal. This section is a crucial, unflinching reminder that being a photographer today requires the ethical imperative to act as a partisan against indifference, observing the mechanisms of control and resistance, whether it’s in a conflict zone or a seemingly regulated democracy.

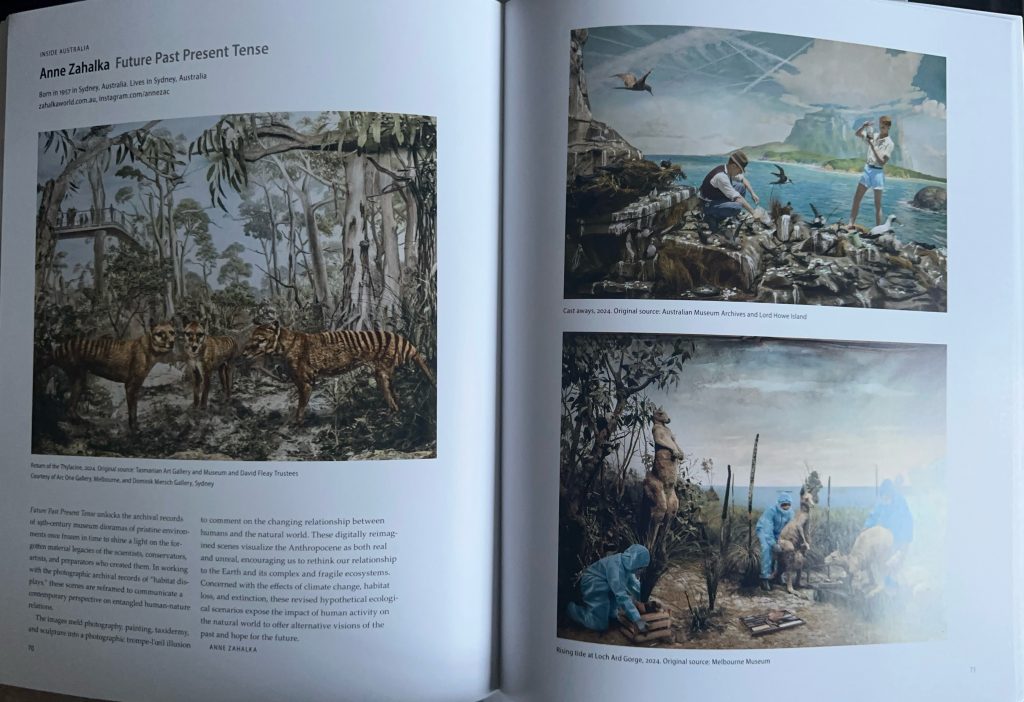

Finally, Rooted Realms, the focus on Nature, directs the gaze “below and above the ground” to examine the planet’s oldest living things in their sublimity, mystical power, and vulnerability to wildfires. This is where the work becomes deeply philosophical, examining impermanence and the environmental crisis with a profound sense of history. Matthew Abbott’s Black Summer immediately captures the brute force of the Australian wildfires. In direct conversation with that sense of destructive immediacy is Mitch Epstein’s Old Growth, a study of imposing individual trees. Epstein’s work, in the context of this issue, becomes a search for a soul settling way of seeing permanence and longevity in the face of ecological collapse. The concept of Dark Ecology, explored in Jhoane Baterna-Pateña’s work, offers the most beautiful and terrifying philosophical framework. It urges us to understand death and decay as integral parts of the ecological continuum, not as an endpoint, but as a visible sign of renewal. Dead trees and the fungi that colonize them are not simply decay, they are the natural recycling system, demonstrating nature’s persistence, life making space for itself, and death enabling new life. Hubert Humka’s The Eternal U reinforces this notion, pushing us to understand that we are all part of the “mesh”, an entangled network where becoming, death, and rebirth proceed in cycles. It is a view that is “dark,” yes, but ultimately an illuminating approach to true ecological awareness.

This issue of European Photography is more than a magazine; it’s an artistic and philosophical intervention. By examining AI, Politics, and Nature through these exemplary, conceptual approaches, it provides the roadmap for contemporary practice. It forces every reader, especially those of us who carry a camera, to confront the three defining anxieties of our time and decide where we stand. It’s a poignant, unflinching look at the world that demands an active, ethical response, leaving me with the knowledge that the aesthetic challenge is inseparable from the ethical one.

Regards

Alex