There are some photobooks that function as critical analyses, and others that function as windows. Then, very rarely, there are books that run as mirrors. Holding Henry Head’s Twelve Acres in my hands for the first time was a strange and poignant experience, a real feeling of nostalgia so specific it felt less like I was viewing someone else’s work and more like I was unearthing a box of my own lost photographs. It threw me back, with startling clarity, to my own late teens. That hazy, formative period when I was still living at home, working jobs for pay to spend rather than for a career, and had yet to even consider going back to college as had no clue what I wanted from life. My days were defined by skating, smoking, and a profound, reckless sense of having not a single care in the world. I played with my hair colour, shaved my eyebrows (I worked as a hairdresser), and generally existed in a bubble of self-discovery, and I saw that exact spirit reflected in Head’s pages.

This book, his debut monograph, is a staggering achievement. On the surface, it is a return to the Ozarks of his adolescence, a photographic reimagining of a defining teenage friendship set against that wild, untamed landscape. Head revisited this terrain, the northwest Arkansas and southwest Missouri of his youth, and has brought back something that feels both intensely personal and utterly universal. It is a meditation on that fleeting moment before adulthood, a “longing to stave off the rupture of entering an adult reality”.

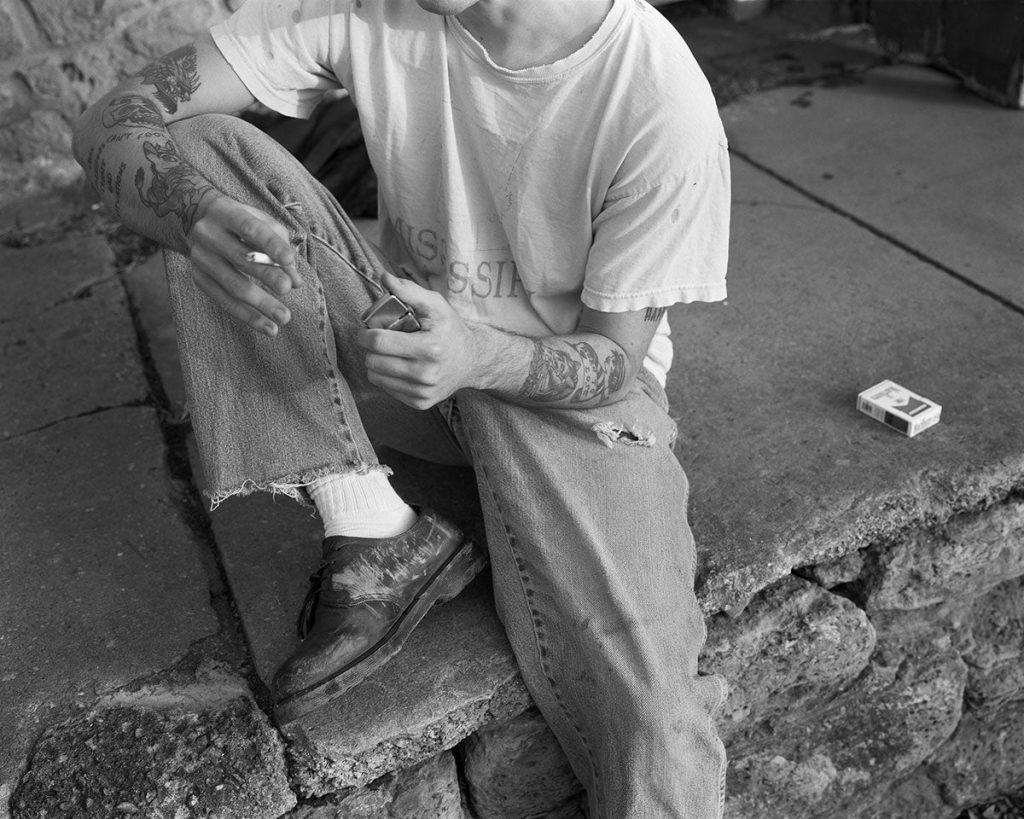

What at once strikes me is the book’s powerful, consistent aesthetic. There is a polished, almost 90s skate magazine quality to the images, a rawness that is both beautiful and unflinching. This is not a sanitised version of youth. It is a portrait of a subculture, a moment I remember so well and would give anything to go back to, a tight crop on a stone ledge, focusing not on a face, but on the artifacts of an existence. We see the tattooed arms, the frayed jeans, the scuffed black shoes, and the ritualistic act of lighting a cigarette. This single frame is pure 90s aesthetic, a familiar, almost sacred pause. This same feeling is there in the intimate, hazy interior of a car, where a figure in a beanie exhales a thick cloud of smoke from an apple pipe. It is the epitome of the road trip vibe, the car as a capsule of freedom, separating the intimate, rebellious act inside from the world outside.

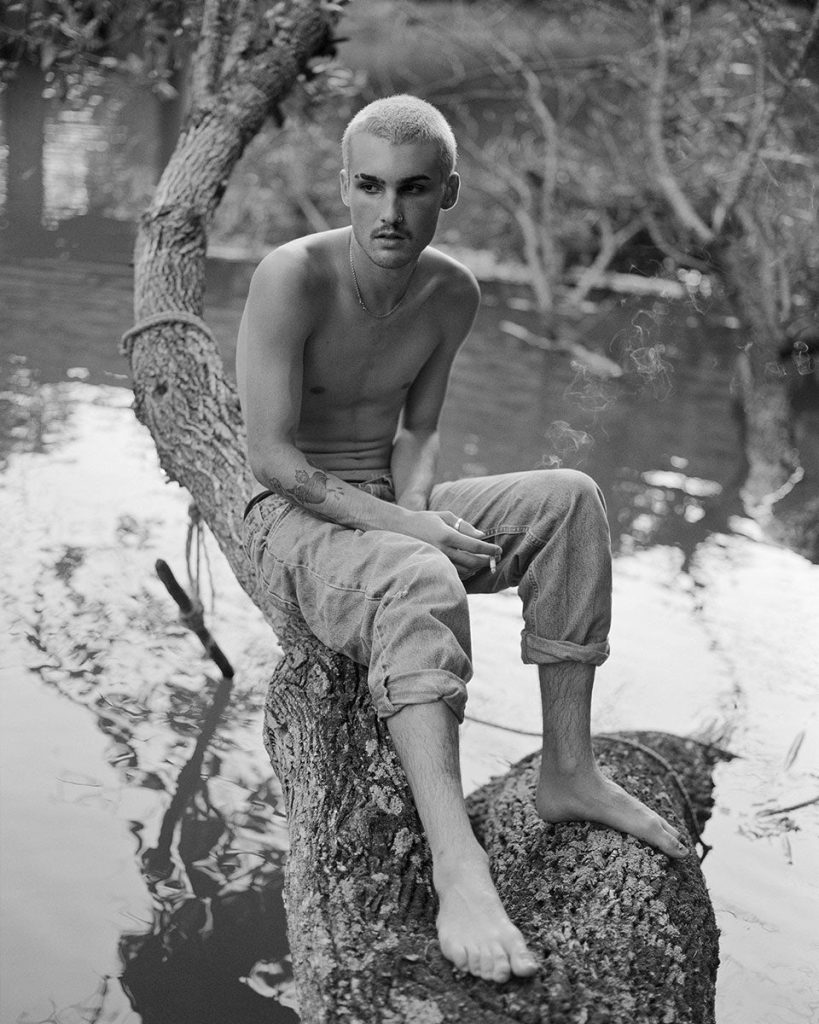

This attitude is embodied in the portraits. A young man with bleached hair and a direct, confident gaze sits on a tree branch over water, a wisp of smoke rising from his cigarette. He reminds me so much of my own friends, of that time when we were experimenting with our identities, trying on new skins to see which one fit.

But the book is not merely about attitude, it is about the landscape of escape. The Ozarks, this “true, wild Ozark countryside,” becomes a character in itself, a participant in the story. It is the place they escape to, “away from institutions and the pressures of social order”. We feel this in a stunning, low-angle shot looking straight up through a chaotic web of bare branches. High in the tangle, two figures are silhouetted against the bright, blown-out sky. It is a quintessential image of childhood exploration, of being “above it all” in a world of your own making. This is the very escape Head himself describes, when he and a friend, both struggling with their own private burdens, would disappear into the outdoors to climb trees and swim in rivers, creating their own imaginary world. That same electric connection to the wild is found in a sun-baked image looking down at the earth, where the photographer’s own shadow, bare foot visible at the edge, frames a small snake slithering through the darkness. It is a random, unexpected encounter, a moment of direct, vulnerable connection to the earth.

The book masterfully balances this quietude with a kinetic, destructive energy. This “not a care in the world” mentality is captured in a visceral, chaotic shot of an explosion in a grassy field. One figure is caught in motion blur, running from the blast, while another stands as a stable anchor, watching. This is the “homemade explosives” and “ringing ears” the press text hints at, brought to life. But this chaos is held in tension with a more pensive, ambiguous feeling. The book presents us with serene, almost abstract moments, like a tattooed arm submerged in water, small minnows swimming around the hand. Yet it also gives us the hypnotic, communal gaze into a bonfire at night, a figure prodding the embers. This is not a neat resolution, but the ritual at the end of the night, a pensive, unresolved staring into the future. It is the perfect note for this journey.

The physical book itself, published by the exceptional Twin Palms, is a weighty, beautiful object. It feels like the “big tomb” I noted, its large 10 x 12-inch format giving the 51 tritone plates ample room to breathe. The clothbound hardcover is elegant, and the uncoated paper gives the images a tactile, material quality. This presentation perfectly honours Head‘s process. It is fascinating to learn how the project developed, evolving from a film collaboration where he used two brothers as “avatars” for his younger self and his formative friendship. He would share his own vulnerabilities and memories, allowing the boys to be themselves, playful, destructive, or bored. He waited for those moments when their present “sparked” with his past, capturing the resulting image. He looked to create a sequence that feels like memory itself, moving from crystal clarity into a more “opaque and distant” fictionalised world, and he has succeeded completely.

In a way, Head had to be making this work for himself, to excommunicate the “imaginary gaze” of an audience, as he puts it, to create something that spoke to him. In doing so, he has created something that speaks to all of us. Twelve Acres does what the best art does. It reflects a deeply personal experience, yet in doing so, it holds up a mirror to our own. It does not matter if you have never seen the Ozarks. This book is about that universal, aching transition, the messy, beautiful, and dangerous process of becoming. It is a book I know I will return to, time and again, whenever I need to remember that wild, untamed, and essential part of myself.

Regards

Alex