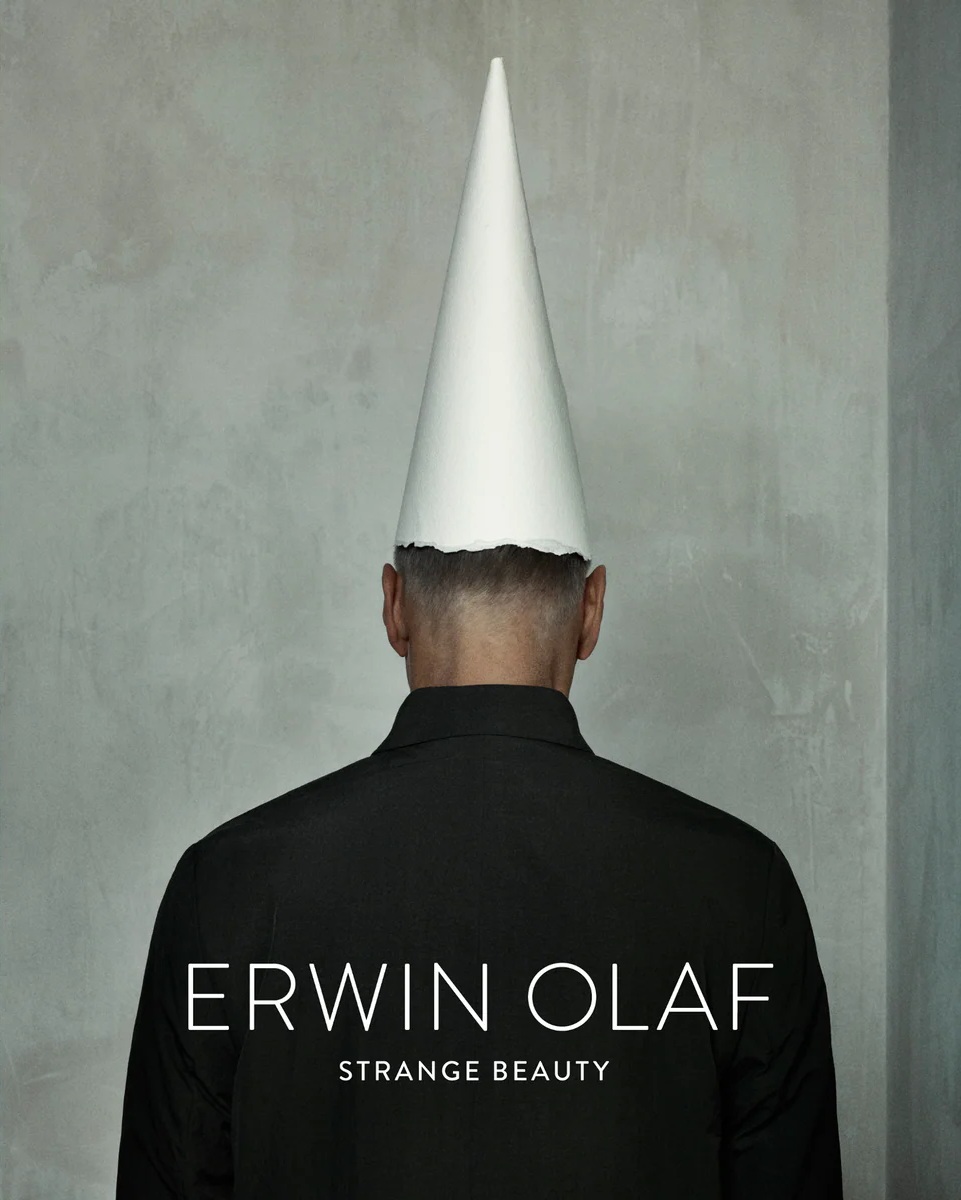

The encounter with Erwin Olaf’s Strange Beauty is a heavy dose of artistic embarrassment. I have to admit that I hadn’t truly grasped how big a name he is in the photographic world, which is a failing I feel keenly, especially when the work itself is so meticulously brilliant. But the immediate, impact of turning these pages was instantly transformed when I found out that Olaf had only passed away two years ago, aged sixty-four. This simple, sobering fact cast a new, poignant spin on the entire retrospective, changing the book from a celebration of an ongoing career into a fixed, final statement. It was like I was now looking through the definitive body of work of an artist who would never get the chance to pick up his camera and make art again, and that instilled an unsettling clarity in every frame. This book and its melancholic weight show the power of the constructed moment, the one built with meticulous discipline to outlive the man who staged it.

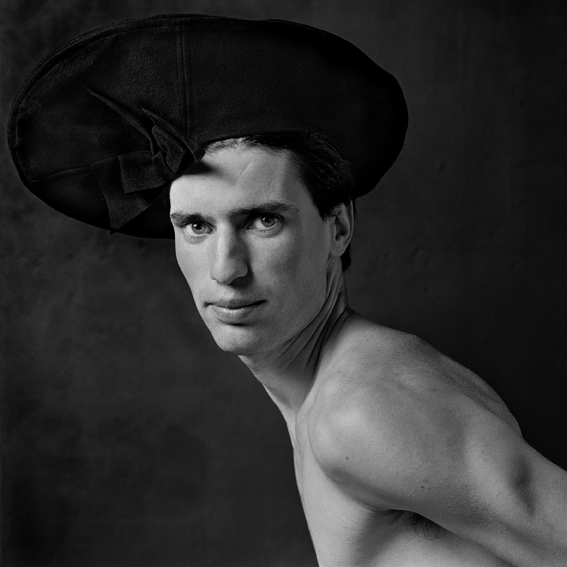

The book takes us right through a breathtaking history of his amazing projects, from the immediate, raw social commentary of April Fool 2020 to the dark, hyper stylised provocation of Royal Blood, all beautifully accompanied by excellent text. Daniel Hornuff’s essay, Consumption and Clowns in Erwin Olaf’s Work, is particularly incisive, helping to decode the central key theme of his career, The Politics of the Staged. Olaf is a master illusionist, showing us precisely how artifice, hyper control, and the perfect, glossy aesthetic can be used as a political weapon to critique the very consumer culture it mimics. He uses the visual language of the film and advertising industries, but his purpose is not to sell, it is to expose, often employing figures like the clown or Pierrot to introduce a dose of tragicomic absurdity. This strategy is nowhere more close to the bone than in the Royal Blood series, where he takes figures like Princess Diana and Jackie Kennedy Onassis and transforms them into monuments of celebrity martyrdom, confirming that his work doesn’t just capture a scene, it shocks you, makes you smile, and forces you to appreciate art all at the exact same time.

This aesthetic discipline is used across all his thematic explorations. In the Grief series, for instance, he perfects the art of the manufactured melancholy, freezing the pivotal, agonizing second after a trauma has landed, setting the scene in a meticulous domestic interior that acts as a kind of psychological theatre. Conversely, his unflinching look at the human timeline in the Mature series is a vital philosophical declaration, demanding dignity and beauty for bodies that are often made invisible by the media. The straightforward honesty of the portrait Claudia S., 63 challenges the tyranny of the perfect facade and offers a kind of soul settling way of seeing that one’s life is still intact.

What makes this book a triumph is the marriage of Olaf’s technical discipline with the surrounding intellectual framework. The sheer arresting power of his images stems from what the essays rightly call his cinematic technique, he doesn’t take pictures, he shoots scenes. His whole philosophy, as he once noted in an interview, was trying to “tame reality to become my dream world.” This is why he felt the need to go outside the studio and create series like Berlin and Shanghai. I love his description of Shanghai as “a very large young girl who is eating everything emotions, space, private life,” a statement that perfectly captures the visceral dynamic of a rapidly changing world and his own response to it. Even his late career confrontation with the brute force of nature in Im Wald (In the Forest), a monochromatic, high contrast exploration of the sublime, shows an artistic courage that inspires me to push the boundaries of my own comfort zone. His move outside the studio was a relentless commitment to pushing the very edges of his own creative frame.

This combination of high art aesthetic control and genuine human connection is perhaps best summarized by a simple anecdote he shared, cycling through Amsterdam, feeling uncertain about his latest work, a very normal man called out to him, “Hey, you! Erwin! You… Respect for your talent, respect for everything you do, keep on going man!” That moment of poignant affirmation from an average person, cutting through the high art anxiety, captures the true power of his work. Erwin Olaf’s Strange Beauty is not just a book of photographs, it is a meticulously preserved final testament to the power of artifice, proving that even as artists pass on, their electrifying compositions remain to challenge our shame, our silence, and our profound human desire for both control and emotional release.

Regards

Alex